Being a dressage trainer in Northern Virginia means working with lots of riders with a jumping background, whether they’re still actively participating in the hunters, jumpers, eventing or foxhunting, or transitioning from any of those disciplines into being a straight-up dressage rider.

Obviously good position for each of those disciplines is different, but they have a few things in common, and riders I teach coming from those disciplines are predictable in the equitation struggles they have to overcome.

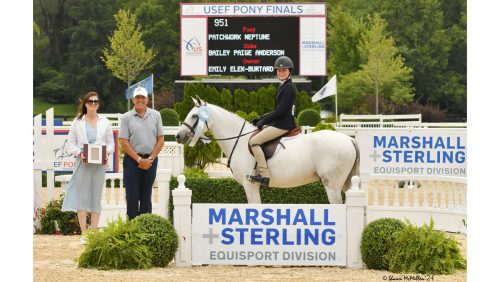

The Chronicle’s intrepid hunter/jumper intern/now staff member, Ann, came to play Dressage Queen with me, and she was no different than any of the others like her that I’ve taught.

She had the benefit of sitting on my Dorian Gray, an 8-year-old Dutch gelding that I’ve trained for two years and who came from an exceptional eventing and dressage program before that, so he’s not unfamiliar with the type of good jumper flatwork riding that Ann brought to the table.

Here’s the common threads I find in teaching riders like Ann, coming to dressage from a jumping background.

– Leg and position. Here is, in a very broad way, what good jumping position looks like: hip angle closed, knees and ankles rolled in such that the rider’s weight is primarily on the thumb toe side of the foot, and upper body forward. This allows the rider to be balanced and organized hovering over the tack such that she can get into or out of it according to the size of the fence.

Here is, in an equally broad way, where that’s bad for dressage position: dressage riders keep their weight more on the pinkie toe side of the foot, with the knee rolling away from the horse. Because we are, for all intents and purposes, never out of the tack, we want to make sure we don’t pinch with our thighs and knees, because that can pop the rider out of the saddle like a clothespin on a bowling ball.

That ankle rolling into the outside of the boot and that weight coming onto the outside of the foot lets us wrap our legs around our horses (think bowlegged) so we can use our leg to help lift our horses’ bellies up—for a dressage rider, leg pressure doesn’t just mean “go;” it can also mean “lift,” like a pair of Spanx, to draw the horse’s belly in towards the back.

ADVERTISEMENT

– Posture. As part of good position, every jumper rider on the planet brings the upper body forward, over those closed hips. And then they ride with me, where I tell them three trillion times to bring their upper bodies back.

This is followed by a vaguely panicked look from the rider, and sometimes some variation on a theme of “But if I lean back any further, I’ll fall off!” Then they look in the mirrors and see that they are still not even close to perpendicular to the ground. And I chuckle to myself.

Sometimes a jumper convert will throw their shoulders back, but not open their hips up. This makes them arch their back significantly, which isn’t an asset for us. I tell my students to lean back like they’re sitting in a recliner, and then to try and tuck their tailbones underneath them. I almost always get the panicked look at that.

– The purpose of the reins. Some of my hunter, jumper and eventer converts are rockstars at contact, and some have no idea what that’s all about, so I draw no sweeping conclusions about contact.

But what all my jumping riders do have in common is that packaging the horse comes primarily from the reins, likely because they just don’t use their seats in the same way dressage riders do (which is easy to understand—their seats aren’t in the saddles like ours are!). I find nearly all jumper riders to use the reins straight back, against the back of the mouth.

Unless I need to emergency stop, I think about using the reins down, more against the bottom teeth. And I don’t mean setting my hands down on my knees; I just mean thinking about pressing the bit down from my fourth finger and forearms.

My jumper students also tend to throw the reins away when sending a horse forward. This makes logical sense: if the reins mean whoa, and I want more go, I should release the reins, right? But as a dressage person, throwing the reins away throws the horse away. It opens the door for the horse to spill onto the forehand; he should be able to hustle into a contact.

– The seat. Ann didn’t report back to me after her lesson about whether or not she was sore, but I can guarantee you she was. (Sorrynotsorry.)

ADVERTISEMENT

This, at the end of the day, is the biggest struggle I see my jumping sport converts go through: we DQs SIT, in ways that even the biggest, strongest, badass-iest jumper rider doesn’t. And of course she doesn’t—I can tell you from personal experience, from my brief (and abysmal) foray into the intercollegiate hunters, that sitting down mid-fence is bad. Bad bad bad.

And that was at 2’3″. But when a dressage rider needs more collection, they sit harder. And when a dressage rider needs more go… they still sit down and drive.

When Ann would feel like Dorian was about to break to trot on her in collected canter, she’d lighten her seat and open the reins. He went forward, sure, but forward, out of the contact, onto his forehand, and almost always then immediately broke to trot anyway.

Nothing that my jumper students bring to their dressage conversions is about being a “bad rider.” It’s just about different.

So if you’re thinking of giving dressage a try, jumper folks, here are the major things to try and remember: body open (by leaning your torso back, by taking your knee away from the saddle a bit, by taking your ankle away from the horse to step on the outside of the foot), and seat and butt closed (by keeping your tummy muscles drawing in towards your spine, and actively drawing the back of your bum into the tack).

And a Starbucks bribery will always be appreciated, though you’ll still be sore the next day!