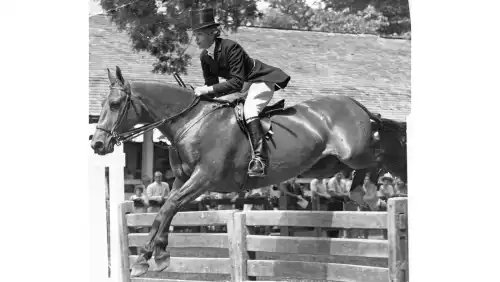

In 1971, a leggy young Appendix Quarter Horse gelding named Texas caught the attention of the crowd at the Calgary International Horse Show (Alberta) when he veered sharply off course and jumped out the in-gate.

Spectating at the event was rancher and equestrian Jack Simpson who, according to his son, Canadian team show jumper John Simpson, was an “aficionado of jumping horses.”

Seeing something in the 16.2-hand youngster other than gate-sour behavior, Jack offered his owner a trade for one of his own horses. She accepted, and Jack took 5-year-old “Texas” home to the family’s cattle ranch, Simpson Ranching, Ltd., in Cochrane, Alberta.

Jack and his son, who was in his early 20s, dabbled in training and competing jumping horses. Jack had recently been the first person to import horses to Alberta from Germany, and John was having some local success showing one of the German mares.

But it was fall, and the Canadian winter was looming.

“We just put him out to pasture,” said John, who, now in his mid-70s, still lives on and operates the family ranch. “Then when spring came around, my dad said, ‘You ought to try that horse out.’”

At the time, most of the horses competing in both North America and abroad were Thoroughbreds, John explained. But there was something different about Texas that John was drawn to. And John was impressed by his breeding: The gelding was sired by the Thoroughbred stallion Chittagong by Royal Charger and out of the Quarter Horse mare Cupid’s Bullet.

John and his father realized quickly that while Texas was a talented jumper, he was seriously lacking in self-confidence. The gelding was afraid of being by himself, whether in the barn, the field or the paddock, and the Simpsons had to learn to work with that fear.

“He hated working alone,” John said, “so we’d drag another horse out when schooling him.”

When it came to the gate-sour habits that earned Texas a new zip code, John and Jack recruited one of their employees, Paddy Farrell, to stand at the gate when John rode. If Texas veered away from the course and toward him, Farrell would “chase him away from the gate with a rag,” John recalled.

In 1972, John was one of five young Canadian riders invited to Toronto to train with some of Canada’s elite show jumpers, including Jim Elder, Frances Rowe and Jim Day. After a summer in training, John felt ready to take Texas on the road, and to advance his own riding career onto the international stage.

“That was the start of Texas,” John said. “When we got him confident enough to get past the gate, he turned into a really good horse. Then off we went on this magical tour of jumping around the world.”

In the early 1970s, the pair competed throughout Canada and the U.S. West Coast, winning reserve champion in the Los Angeles Horse Show in 1972, and a number of top-three placings at horse shows around Canada, from Calgary and Edmonton to Toronto and Montreal, between 1973 and 1976.

ADVERTISEMENT

“When we got him confident enough to get past the gate, he turned into a really good horse. Then off we went on this magical tour of jumping around the world.”

JOHN SIMPSON

John entered Texas in a number of puissance classes, including clearing 6’4 ¾” to win at the 1976 Washington International Horse Show (Maryland).

“The highest we ever jumped was 7’2”, John said. “The rider can’t see over it, so the horse sure can’t either. That’s one of those things where you have just got to get it right.”

The Canadian and his unlikely Quarter Horse jumper had a breakout year in 1977. They traveled overseas and won the Grand Prix of Rotterdam at CHIO Rotterdam (the Netherlands) and placed third at both the Embassy Filter Stakes at Hickstead (England) and at the Grand Prix of Ireland at the Dublin International Horse Show—a class won by current U.S. show jumping chef d’equipe Robert Ridland that year. Texas also had a number of top-three finishes at major Canadian shows as well, including winning the grand prix at the Spruce Meadows ‘Masters’ (Alberta), a venue that John frequented because it was so close to home.

John and Texas’s winningest year was 1978. They were eighth overall—the top Canadian pair—at the FEI World Championship in Aachen (Germany), where the Canadian team finished fourth.

That fall, he and Texas had a blazing hot two weeks. At the Washington International Horse Show, they were members of the Canadian team won the Prix de Nations class—the equivalent of the modern Nations Cup. John and Texas didn’t have to jump the second round because Canada was guaranteed the win—a lucky break because Texas, as the anchor and only horse left behind, was in the barn, panicked, never having fully overcome his fear of being alone.

Nevertheless, the pair went on to win the President’s Cup Grand Prix class at the same show. The next week they traveled to Madison Square Garden and the National Horse Show, where they won the Grand Prix of New York.

“He wasn’t just one of those ring horses,” John said. “He was a horse you could go out and do something with.”

At home on the family’s ranch, it wasn’t unusual to see John wearing his cowboy hat and Texas sporting a western saddle to help work cattle.

“I’m just a cowboy from the West,” John said. “And I think being out of the ring chasing cows was one of the best things for his mind.

“Too many people just ride around in circles,” he continued. “If you start trotting up and down hills, you’ll see you can get a horse fit pretty fast!”

But while Texas was versatile and flexible under saddle, he wasn’t so easygoing in the barn.

“I’m just a cowboy from the West. And I think being out of the ring chasing cows was one of the best things for his mind.”

John Simpson

“He was an animal in the box,” John said. “He’d eat you as soon as you walked by. We had to have a double box stall and something across the top so he couldn’t get out [when he traveled].”

ADVERTISEMENT

“But as soon as you got him out, he was all business,” John continued. “Lots of people wanted to buy him, but he wasn’t for sale, so I got to do all the riding. He was a real pleasure to ride.”

In 1979, John and Texas made the Canadian team for the Pan American Games in Puerto Rico, but Texas struggled with the arena’s deep sand footing. They missed their chance at riding in the Olympic Games when Canada joined the U.S.-led boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics. But the pair continued to show successfully closer to home.

In December 1981, John and Texas were featured on the cover of The Chronicle of the Horse. But also that year, Texas suffered an injury that would end his career.

“He injured something between his hips,” John said, “and we never could figure out what it was.”

Texas lived out the rest of his life on the ranch that he loved. And when he died, John said they buried the gelding on the ranch “in a special place.”

After Texas’s injury, John said, “I went off in the world to find more like him.”

And he did, purchasing Texas’s younger half-brother, aptly named Dallas, whom he competed successfully for several years.

John retired from show jumping in 1982 but still lives and works with his family on the ranch, which has expanded to about a thousand head of beef cattle and 15-20 equines, most of whom are Quarter Horses.

“I had a lot of fun years riding around the world on a Quarter Horse,” John said. “That was really my first attraction to them. And where we live, that’s just the kind of horses there are.”

Two of John’s grandchildren inherited the family horse bug.

“The youngest one, who is 5, was out chasing cows on her pony last summer,” he said. “And both are currently into cattle penning, and both were at a jumping stable recently for riding lessons.”

And should his grandchildren decide to pursue more English pursuits on horseback, it’s likely John will take his own advice: “I always tell people to keep their eyes open,” he said. “You never know where you might find another really special horse.”