In honor of Women’s History Month, we look back at the legacy of women in equestrian sports—and in the pages of The Chronicle of the Horse—from racetracks to Olympic stadiums.

A little more than 50 years ago, President Richard Nixon signed into law the Education Amendments Act, which contained these 37 words in the form of an amendment submitted by Senator Birch Bayh, a Democrat from Indiana: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

The amendment, which was an effort to prevent sex discrimination in education, became Title IX in the legislation. And although none of those 37 words are directly related to sports, they caused a tectonic shift in the landscape of women’s athletics when it became apparent that Title IX also applied to school sports programs.

The generations of girls who came after Title IX, who grew up in youth soccer leagues or on traveling swim teams, would be astonished to know that, in the not-too-distant past, girls weren’t “supposed” to play sports, just like they weren’t supposed to pursue advanced degrees, have careers of their own, or even have their own checking accounts.

Title IX became law just a few years after Kathrine Switzer became the first woman to officially run the Boston Marathon in 1967, although she’d entered using her initials. Race organizers had no idea they’d allowed a woman into the race and tried to physically drag her off the course. (Women were considered too fragile to run 26.2 miles at the time.) Title IX was enacted the year before the 1973 “Battle of the Sexes” in tennis, when Bobby Riggs, a top men’s tennis player in the 1930s and ’40s, asserted that women’s tennis was so inferior that even at age 55 he could defeat the current top female players. He lost to the legendary Billie Jean King.

Also in 1972, at the Munich Olympics, just 14.6% of athletes were women. Women weren’t permitted to compete in the marathon at the Olympic Games until 1984, and they didn’t have their own World Cup soccer tournament until 1991. That same year, the International Olympic Committee began to require that all new Olympic sports include competition for women. By the Tokyo Olympic Games, held in 2021 after being postponed a year due the coronavirus pandemic, female participation had climbed to 48.7%.

Likewise, the participation of women in college sports has skyrocketed. A report issued by the NCAA last year marking women’s progress in the 50 years since Title IX found that the overall women’s participation rate in college athletics was 43.9% in 2020, compared to 27.8% in 1982, when the NCAA started hosting women’s championships across divisions.

But even after a half-century of Title IX, the women’s national soccer team was just granted equal pay in late 2022, and it took a viral TikTok video showing disparities in the men’s and women’s weight rooms at the NCAA college basketball tournaments for women to finally earn equal billing and share the “March Madness” moniker.

Women’s professional sports have been battling for media coverage for decades. A joint study by researchers at the University of Southern California and Purdue University (Indiana) has analyzed media coverage of women’s sports every five years since 1989. The most recent sampling, from 2019, found that 95% of total television coverage, as well as the ESPN highlights show “SportsCenter,” focused on men’s sports.

At the end of 2020, Liz Halliday-Sharp became the first woman to win the USEA Rider of the Year award in nearly 30 years. Lindsay Berreth Photo

The researchers also pointed out that the actual coverage of female athletes, when they are covered at all, is different. In the 1990s, they noted that reporters and sportscasters (almost entirely men) often trivialized, sexualized and insulted female athletes. By the 2010s, the coverage had become more respectful but also rife with what the researchers termed “gender-bland sexism”—coverage that seemed perfunctory, lacking the genuine enthusiasm and admiration shown for the performances of male athletes.

Unique In Sport

Horse sports, however, have always been a unique beast. From the Chronicle’s earliest days, women have been pictured and mentioned in the magazine for their competitive successes right along with men, in seemingly comparable, if maybe not exactly equal, measure. Although the biases of the times are just as visible in our pages as anyone else’s, the horse has always been a great equalizer—if you were a woman on a good horse, judges would pin you; you’d be right up front hunting in the first field, and you might get picked for an Olympic team—once the Olympic equestrian sports opened up to women, that is.

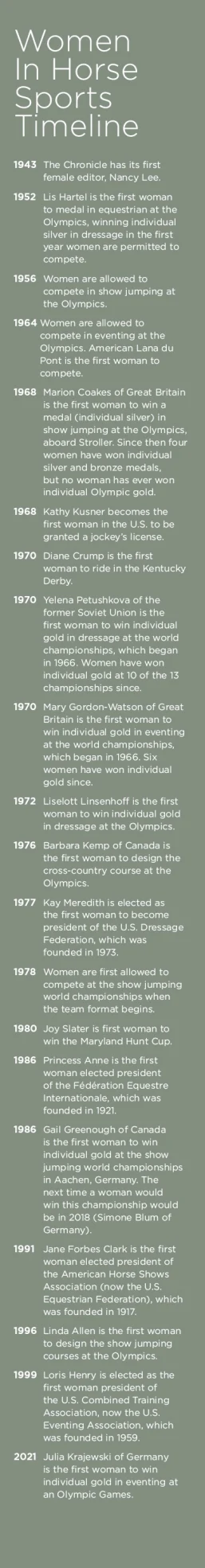

It wasn’t until 1952 that the IOC allowed women to participate in equestrian sports. The Fédération Equestre Internationale decided women could participate in dressage and considered, but decided against, allowing them to compete in show jumping. (Their participation in three-day eventing wasn’t even on the table at the time and wouldn’t be allowed until 1964.) At those 1952 Olympics, in Helsinki, Finland, four women competed, and one of them earned individual silver. Lis Hartel of Denmark was notable not only for being the first woman to earn an Olympic medal in direct competition with men but also for being a survivor of polio; she was paralyzed below the knee.

Hartel won individual silver again in 1956 in Stockholm (Sweden), when women comprised 11 of the 36 individual starters in dressage and two of the three medalists. (Liselott Linsenhoff of Germany took bronze.) Women competed in show jumping for the first time at these Games, with Patricia Smythe of Great Britain becoming the first female medalist, earning a team bronze and placing 10th individually. From the moment they were allowed in the Olympics, women were not only competitive; they were serious medal contenders.

ADVERTISEMENT

Several times during the 1950s and early 1960s, the FEI considered, but ultimately decided against, proposals for separate Olympic competitions for women and men. They also debated allowing women to compete in jumping world championships but decided instead to hold a separate women’s championships. The short-lived competition occurred in 1965, 1970 and 1974 before being abandoned in 1978 in favor of the modern world show jumping championships format, with men and women competing together, and the addition of the team competition.

The Chronicle’s international coverage wasn’t nearly as robust in those years, and there doesn’t appear to be much discussion of women’s inclusion in international championships. An Aug. 15, 1952, editorial discussing the moderate success of the first civilian U.S. Olympic teams at Helsinki encouraged show managers to help grow the sport at the top levels, but it makes no mention of women competing for the first time. (The dressage competition at those Olympics and Hartel’s historic medal wasn’t even covered in our pages; we just ran the results.)

The editorial, entitled, “Now Is The Time To Work,” read in part: “Great Olympic teams are not going to be made by picking the top few men in horsemanship and making Olympic competitors from them overnight. Such teams of the future must come from a sympathetic understanding of the difficulties of the job by everyone even remotely interested in horses, so that the shows, the race tracks, the hunting fields, the polo fields, the point-to-points and the hunter trials will all be willing to put their shoulders to the wheel to build up a great ground swell not just in the box seats but in the farm lots.”

In 1964 in Tokyo, American Lana du Pont was the first woman to compete in the Olympic three-day event. Her teammate, Michael Page, penned a summary of the competition in the Nov. 20, 1964, Chronicle.

“Lana du Pont was faced, not only with riding in her first Olympic Games, but also with being the first and only woman competitor in an Olympic Three Day Event,” Page wrote. “The pressure of competition was understandably greater on her than it was for the rest of us. Her competent over-all showing is sufficient answer to those thinking that women cannot compete on equal footing in this event. The apparent popularity of the Americans with the Japanese was due in no small measure to the excellent regard with which Lana & Mr. Wister were held as part of the Team.”

Du Pont finished 33rd individually from 48 starters, and the U.S. team took silver.

The Chronicle’s coverage of the Olympic show jumping in Tokyo noted that, “Miss [Kathy] Kusner was the first woman rider and this brought loud applause as she entered the ring. In addition to [her American teammate] Miss [Mary] Mairs, there were two other feminine jockeys—a total of four women riders.”

From The Arena To The Racetrack

Kusner was one of the most successful American show jumpers of the era, representing the U.S. at the 1964, 1968 and 1972 Olympics. The Chronicle also covered her quest to get a jockey’s license from the Maryland Racing Commission.

In a “Living Legends” profile of Kusner in the April 4, 2016, issue of the Chronicle, she recounted how she rode timber horses for Dr. Joe Rogers. “He knew what I really, really wanted was to ‘ride in the afternoon,’ or races at the track—with a jock’s license. One day he told me he now believed I would be able to do it, on account of the Civil Rights act having been passed,” she said in that article.

The landmark 1964 legislation outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

“I thought, ‘Well, one of these racetrack girls will do it.’ There were girls at the track on the backside working that were light enough. Their whole life was that. I had this other life too with the United States Equestrian Team, sneaking away for short times to do whatever I could with race horses, so of course one of these girls would do it, and, of course they didn’t,” Kusner recalled.

ADVERTISEMENT

Four years passed, and in 1968 Kusner tried to get her license. She appeared before the Maryland licensing body three times and was denied each time.

“No License For Kathy” was the headline on a news item in the Feb. 16, 1968, Chronicle, which read: “Kathy Kusner’s application to become a woman jockey was denied by the Maryland Racing Commission on Feb. 8.

“Stewards who watched Miss Kusner work out horses at Pimlico reported to the commission by letter. J. Fred Colwill said in his report that Kathy ‘does not have the ability to ride professional in races in the afternoon.’ He stated that Miss Kusner ‘rides high in the irons and did not give me an impression of strength and authority.’ ”

“I had already ridden in two Olympic Games, but I couldn’t ride well enough to get a jock’s license. They would have rather died than give me or any girl a jock’s license,” Kusner recalled in the 2016 profile. She finally took the case to court, where a judge granted her a license in a matter of minutes.

Kusner mostly rode in foreign races, where she was able to get better mounts, but in 1971, she became the first woman to ride in the Maryland Hunt Cup.

“No one could question the presence of Whackerjack. He is a fine jumper. Many, though, questioned the presence of his rider, Kathy Kusner, the first girl rider in the history of the Hunt Cup,” read the Chronicle’s coverage of the race in the May 7, 1971, issue. “Let’s not argue the pros and cons of girl riders. Suffice it to say that Kathy is the best and that any horse in the race would benefit from her skill. At the same time, though, Whackerjack was at a distinct disadvantage. Kathy had to carry fifty pounds of lead and dead weight, especially this staggering amount, must be construed as an unsurmountable disadvantage.”

In 1971 Kathy Kusner became the first woman to ride in the Maryland Hunt Cup, aboard Whackerjack. Douglas Lees Photo

Not quite a decade later, a commentary in the May 2, 1980, Chronicle by editor Peter Winants, titled simply “Women,” celebrated the first woman to win the Maryland Hunt Cup, Joy Slater.

“Ah, here’s a delicate subject, one hardly fitting for a male editor to address, but for better or worse, here goes,” he began. “Why women? Simply because females invaded Maryland last weekend with gusto, and their accomplishments are recorded in various sections of this week’s Chronicle.”

Not only had Slater claimed victory in the Hunt Cup, but Melanie Smith (now Taylor) came close to winning the show jumping World Cup Final, held that same weekend in Baltimore. (She finished second to Conrad Homfeld.) And Winants also noted that women—Karen Sachey on Alpine and Torrance Watkins (now Fleischmann) on Poltroon—claimed the top two spots in the open intermediate division at Ship’s Quarters Horse Trials in Westminster, Maryland.

“A womens’ [sic] world? Perhaps, but definitely according to the results of horse sports last weekend in Maryland. Now shut up, Winants. Enough said,” read the last paragraph.

There were more mentions of “firsts” for women in our pages in the 1980s and 1990s. Perhaps the result of more women writers reporting for the magazine? But also an indication that women were still achieving milestones in the not-so-distant past.

In 1984 at the Los Angeles Olympics, one of the watershed moments for American horse sports, eventing saw its first two female individual medalists, 20 years after women first rode in the sport at the Olympics.

Germany’s Julia Krajewski became the first woman to win individual eventing gold at an Olympic Games in 2021 in Tokyo. Lisa Slade Photo

“The American team of Mike Plumb, Karen Stives, Torrance Fleischmann and Bruce Davidson rode brilliantly to narrowly defeat the World Champion British by 3.2 points as Stives came within one show jumping rail of being the first woman to ever win the individual gold in the Olympic three-day event. Still, she and Virginia Holgate of Britain, who took the bronze behind Stives and gold medalist Mark Todd of New Zealand, were the first individual female medalists in this discipline,” wrote John Strassburger.

It would take until the Tokyo Olympics for a woman, Julia Krajewski of Germany, to win individual eventing gold. “I really didn’t know that no female had ever won gold, because of all the great ladies in our sport. I thought someone must have done it,” Krajewski is quoted as saying in the Chronicle’s coverage. “First of all, I think it’s about time. It’s fitting in the time we’re in right now. It doesn’t matter where you come from or whatever else, I think everything is possible, and everyone who has a dream and a passion should go for it. Nothing can really hold you back if you really want to go for it and work hard for it.”

This article appeared in the Spring 2023 issue of The Chronicle of the Horse Untacked. You can subscribe and get online access to a digital version of COTH and then enjoy a year of our lifestyle publication, Untacked, also. If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content.