In honor of Kathy Kusner receiving the U.S. Equestrian Federation Lifetime Achievement Award, we are republishing this Living Legend article that graced the cover of the April 4, 2016 Chronicle of the Horse.

The Southern California light transitions to rose gold as the sun begins to slip behind the Pacific Ocean. Our day began nearly 12 hours earlier, and now we’re slowing down, strolling near a playground by Kathy Kusner’s home in Los Angeles.

Children shriek and scamper about, chasing each other, the swings squeaking their familiar back-and-forth song.

“I love this,” Kusner says watching them. “Every race of little kids playing together. Having grown up in the South during segregation, which I always hated, I love seeing it, all the colors of people and so many beautiful mixed race couples; it’s so great! Look at all these kids, everybody together and nobody noticing. Being normal. It’s heavenly.”

A true humanitarian, Kusner has lived her life refusing to acknowledge barriers or accept prejudice, be it for herself as a woman or racially, religiously or sexually on behalf of others. Hers is a life forged by a quiet boldness and fueled by joy and curiosity.

She’s litigated for her right to ride in sanctioned races at the track, competed as one of the first of two women on the U.S. show jumping team in the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo, followed by representing the United States at the next two Olympics. She’s helped at-risk youth in Watts and the surrounding neighborhoods through her Horses In The Hood non-profit organization. Run almost too many marathons and ultra-marathons to tally. Become a pilot. Attended Alcoholics Anonymous and Cocaine Anonymous meetings simply because they “are wonderful for humanity,” even though she has never tasted a drop of alcohol, experimented with drugs, nor has any addicts in her family. Scuba dived. Studied sign language, just because. Audited courses in geology, American history, traveled the world.

Spending time with the vivacious Kusner is just plain fun, as is experiencing the world through her multi-colored prism. Not rose-colored. She isn’t a Pollyanna or a simple do-gooder. Nor is she color blind. She is the opposite. She sees color, celebrates diversity and loathes any form of discrimination. And she finds adventure everywhere.

Spitfire

Kusner insists on picking me up at my hotel near LAX on the morning of our interview. She has carefully planned an entire day for us, graciously allowing me a peek into her world. There have been emails back and forth wondering if I am a runner (I am not). At almost 76, she still is, logging 4-5 miles a day. She even drove to a local hotel prior to my arrival to check on their prices and availability although I could have easily called.

Thoughtful courtesies like this continuously infuse our day.

Despite this, she is a reluctant subject. It’s just not her nature to discuss herself. It isn’t because she is shy. Kusner is the opposite of shy, humming with vitality and humor. She is, however, truly humble.

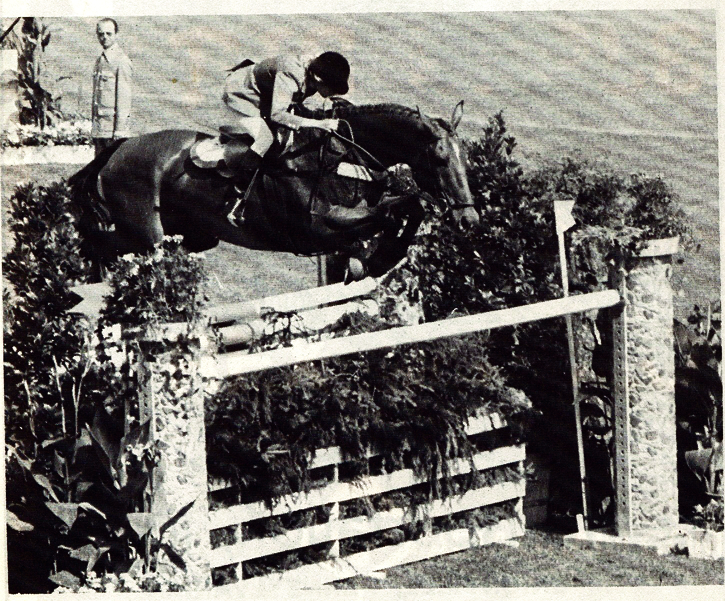

Untouchable was one of Kathy Kusner’s most famous partners, competing with her in the 1964 and 1968 Olympic Games, 1967 Pan American Games, and winning grand prix classes all over Europe, as well as the 1967 Ladies’ European Championship. She called him “the best horse of my life.”

The story of Kusner isn’t found in the answers to my questions—how it felt to be the first licensed female jockey or a three-time Olympian, or actually being in the sky as the first female pilot hired by Executive Jet Aviation after getting her type rating in a Learjet—but in the quiet (or not so quiet) detours between them during our interview. It’s found in the inquisitiveness with which she engages the world and the decency of her interactions.

Our day begins at the Spitfire Grill, the name of the restaurant painted on an old propeller, located across from the active runway at the small private Santa Monica Airport where, rumor has it, a British World War II fighter plane, a Spitfire, sits in one of the hangars.

Make It Bland

“Don’t write, ‘She said with a laugh or a giggle,’ ” Kusner instructs me good-naturedly over huevos rancheros. “None of that. I hate that. Make it bland.”

Kathy Kusner bland? Impossible.

Kusner had a transient early childhood, moving every year or two with her older brother and parents as they crisscrossed the country following her father who was in the Air Force, eventually settling in Virginia.

It was a household with few rules, which suited Kusner’s independent nature and still-present wanderlust. Curious if her father’s career choice had any influence on her future love of flying, Kusner replies, “Nothing influenced me. I influenced myself. My brother went his way, I went mine, and my parents went theirs. That’s really how it was, and the good part was everybody let everybody do that.

“The one rule,” she adds, “Was I had to be home by dark. When I was a little kid, I was off exploring. I would stagger in at the end, just before dark.”

Omnipresent was her inexplicable love of horses.

“I was just crazy about horses for no reason other than they were horses,” she begins to explain and then interrupts herself as a man walks down the sidewalk next to our outdoor table.

“I wonder if this person knows something interesting?” she says.

“We were told there was a Spitfire on this field. Do you know where?” she asks him, gesturing to the airport across the street.

This foreshadows our day. Her somewhat resigned drudgery in having to discuss herself and accomplishments delightfully interspersed with things Kusner finds far more compelling—engaging others.

Escaping Jail

Born in 1940, Kusner’s teenage years were spent in segregated Virginia, and her enchantment with horses continued, as did her abhorrence of prejudice. Eventually she found her way to a local horse show, watching a world she didn’t know existed, and a passion was given direction.

Not from a privileged background and with no connections to the equestrian world, she began working at a stable in exchange for lessons and $2 a day. The money meant nothing to her, but the lessons did. She was a natural and eventually was asked to ride for others. At first they weren’t the best horses, a range of motley, tricky mounts, but it mattered not. Better horses were offered to her with time. She found work as a groom and, naturally, her fellow grooms became friends. They were all men and black.

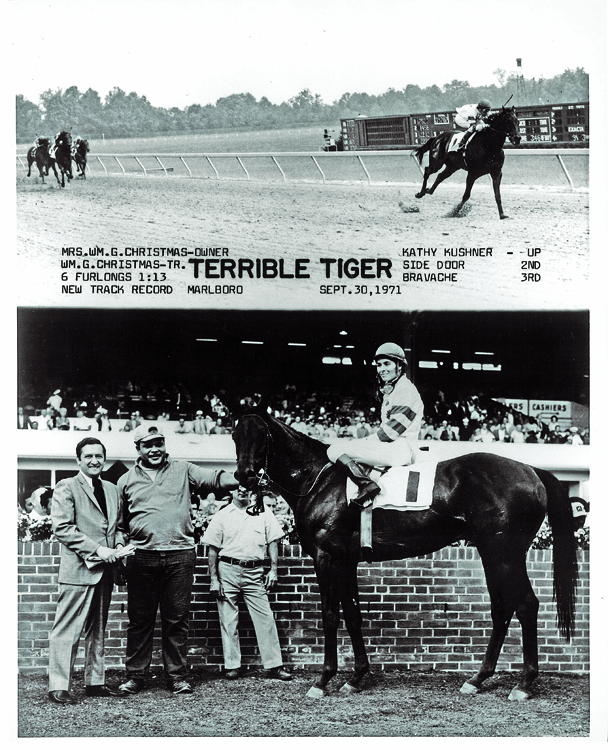

Kathy Kusner rode Viking Stables’ Whackerjack to sixth place in the 1971 Maryland Hunt Cup, carrying 50 pounds of lead. “The night before the race, they tried to stop me. They never had a girl, and they didn’t want to have a girl ride in the Maryland Hunt Cup,” she said. Douglas Lees Photo.

“My favorite people at the shows were the black grooms. They were my best friends. We would ride together in the van to horse shows, braiding or whatever, and occasionally someone would ask, ‘Do you want to ride something in something?’ and I would say, ‘Yes sir!’ and leap into my riding clothes, but mostly I was just braiding and things like that,” she says.

“We were in the van, and it’s lunch time, and there is a diner. They couldn’t even go into the diner to order, much less eat. I took their orders and brought the food back for all of us. I loved them and hated that they couldn’t do the same things as white people do. Segregation was terrible,” she recalls.

As her skill and passion for jumping grew, Kusner was also captivated by horse racing in equal measure.

“The Culpeper show used to have racing on Saturday and Sunday and also a pony race. There were two ponies needing jockeys. One looked like a little Thoroughbred, and the other was a pile of hair. The little Thoroughbred got taken by some other little kid, so I got the pile of hair,” she says.

The pile of hair won.

She would race again at the same Culpeper show in the following years. She was riding jumpers for dealer Chuck Ackerman in the afternoon, and he had a Thoroughbred they decided to train to run in the Saturday and Sunday Culpeper races.

“I would go at 5 a.m. to the barn before I had to go to jail, which was school. I hated school, and it was hate-able. It wasn’t like today. It was segregated, and you had to wear a skirt. The teachers were boring. It was one big, no-good situation,” she says.

She would gallop the horse in the morning, go to jail, and then back to the barn to school jumpers in the afternoon.

The only races Kusner, being a female, could ride were unsanctioned.

“Everybody riding in the race was drunk. I was the only woman. On Saturday, one jockey threw a brick he had brought to the start at the starter, and the second day, someone else attacked another with a broken bottle in the paddock. I loved it! More action! My plan was to just stay away from everybody, get on the front end and just try to stay there, out of trouble,” she says.

It worked. She won on both days.

Decades-long and dear friend Conrad Homfeld (a member of the 1984 gold-medal Olympic show jumping team) shares, “She goes in 100 percent when she commits to something. She’s not a half-measure person. Whether it was flying airplanes or becoming a jockey or riding show jumpers, she was all in.”

Barter System

Breakfast finished, we make our way across the street to look for the Spitfire. Palm trees line the drive, looking like fireworks frozen in full explosion. We go to the active runway and watch planes take off and land, the ocean in the distance to our left, the Hollywood sign visible on the mountain to our right.

Our visit results in another encounter, a plein air painter from the East Coast, but alas, no Spitfire. The pilots’ lounge is void of “old geezers” who normally haunt the place and couldn’t help in our quest. We continue on our way.

“A lot of my life has been about the barter system,” Kusner says as we pull onto the Pacific Coast Highway en route to Malibu to honor one such arrangement. She insists on driving in the left lane, slowly, a line of cars steadily growing behind us, so as to provide me an unobstructed view of the Pacific.

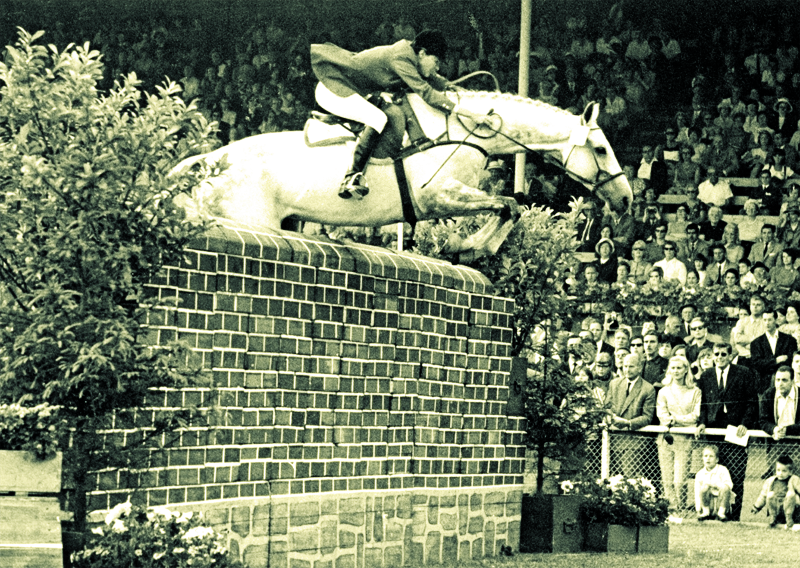

Kathy Kusner rode Fleet Apple to a team silver medal at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. Gamecock Photo.

In exchange for teaching the now longtime friend she met at one of her clinics, Dr. Scott Bateman, he provides her with his medical services.

Similar barters allowed Kusner to earn her many ratings as a pilot.

In the 1960s, she became acquainted with soon-to-be legendary rider and trainer Benny O’Meara.

O’Meara, too, was mesmerized by horses despite having no family history, connections or money. He would show up at the rental stable in Prospect Park, smack in the middle of Brooklyn, grab a broom, and sweep his way into the barn. They would kick him out. He’d return and sweep his way back in. Repeatedly. Eventually they tired of removing him, and he stayed, observing the blacksmiths, the riders. So poor, for lunch he would bring a packet of Kool-Aid to a nearby diner, ask for a glass of water and mix the Kool-Aid in it. For lunch, he would pour ketchup on a paper napkin and eat it.

Within a few short years and no formal training, O’Meara was one of the leading riders and horse dealers in the country. Kusner and O’Meara became a couple, Kusner riding many of his horses and O’Meara focusing more on dealing, quickly making a great amount of money.

“Right away, Benny bought a white Cadillac. In a couple years, he went from eating napkins to buying his first Cadillac. Then he bought a second Cadillac, and it was money green. It had to be money green,” she says.

On a trip to Canada to look at some horses, the Cadillac broke down. They decided to fly commercially, which O’Meara was reticent to do. He took a sleeping pill on the plane before take-off, but on the return trip, he decided he wanted to get his pilot’s license, realizing he could make more money.

“He could get more horses, sell more horses and make more money. That was his goal. Now, making money is of no interest to me, but doing stuff is. Benny started taking flying lessons and said I should too, and he’d pay for them because I was riding his horses. I mean, nobody could ride them better than Benny, but I was riding them and rationalized it that way to myself because I couldn’t have afforded to take flying lessons,” Kusner says.

ADVERTISEMENT

But flying would be the demise of O’Meara when his plane, a World War II vintage Mustang, crashed shortly after take off from an airport in Leesburg, Va. He was 27.

Kusner was at a barn in Maryland when Ned, one of Benny’s brothers, got a phone call at the barn, and he gave her the news.

“It was horrible,” she recalls.

Kusner remains close friends with the O’Meara family, showing me a recent picture on her phone with his sister, Jane O’Meara Sanders (wife of presidential candidate Bernie Sanders). His younger brother Frank O’Meara has always been a very close friend.

Even after Benny was gone, Kusner continued trading in on her riding ability for a chance behind the controls of an airplane.

“I loved flying but never had the money for that. I was later riding horses for the family of Patrick Butler, who developed Hazelden, the best alcohol and drug treatment center in the country. The Butlers offered to pay for my flying in exchange for me doing all concerning their horses. For this chance to fly, I got every rating. Private pilot, commercial pilot, instrument rating, sea plane, commercial sea plane, glider, commercial glider, though I don’t know what you do with a commercial glider,” she confesses.

She even took a helicopter lesson, but it was terribly expensive, and she didn’t feel right asking the Butlers to pay for that too.

During Kusner’s third and final Olympic Games in Munich in 1972, Bruce Sundlun repeatedly showed up at the stable in the morning. He was the president of the Washington International Horse Show (D.C.) and, more fascinating to Kusner, the president of Executive Jet Aviation (now NetJets). Kusner hadn’t planned on showing at Washington that year, following six months in Europe and then the Games.

He asked Kusner to reconsider making an appearance. In exchange he offered her the chance to get her type rating at his company in a Learjet.

Kusner spent several months in Columbus, Ohio, getting her type rating. The president of operations at EJA was none other than Paul Tibbets, pilot of the Enola Gay that dropped the first atomic bomb on Japan. It would be Tibbets who would offer Kusner a job with the company (she agreed to become a line pilot for one summer). She was the first female pilot employed by EJA.

“Paul Tibbets was a very quiet, very, very, very nice person. I finally asked him his opinion about dropping the bomb on Hiroshima. He said doing that probably saved a lot of Japanese and American lives. Truman was president, and it was Truman’s decision, but Tibbets, what a nice man,” she reflects.

Flying taught Kusner life lessons applicable to more than just keeping a machine safely in the sky.

Kathy Kusner topped the puissance at the Aachen CHIO (Germany) three times, including in 1967, aboard Aberali. Phelps Images/Collection Poudret Photo.

“One time I was in the simulator and had messed up an instrument approach, so I stopped and pushed the top open and asked if I could start again,” she says. “My instructor slammed the top back down and said, ‘No! In real life you cannot start over again. You have to salvage it!’ Of course! I’ve used that when I am teaching and the horse stops at a jump or you have a wreck. You don’t start over again. You fix it by teaching the horse the correct thing to do.

“That was a fabulous thing to learn, and that is life!” she says.

First Licensed Female Jockey

We’re now strolling around a lagoon in Malibu. Bateman’s riding lesson is over, and Kusner is pointing out various bird species. Somewhat active with the National Audubon Society, she brought two pairs of binoculars for us to use, but perhaps realizing that my bird knowledge parallels my running ability, leaves them in the car. Just bird basics for me.

When I ask if we can return to the topic of her pursuit of a jockey’s license she sighs. “Oh OK,” she says, her disappointment so obvious it causes me to laugh. She would much prefer to continue bird watching and chatting up the people passing by.

It was 1964, and the Civil Rights Act had just been passed. Elated by the new legislation, Kusner was also unaware of the implications this would have on her own life.

“I used to ride timber horses for a great man in Leesburg, Dr. Joe Rogers. He was a wonderful person, and I would ride for him in some timber races, but he knew what I really, really wanted was to ‘ride in the afternoon’ or races at the track — with a jock’s license. One day he told me he now believed I would be able to do it, on account of the Civil Rights Act having been passed,” she says.

So Kusner waited.

For 25 years, Kathy Kusner and the late Craig Chambers were life partners, enjoying, among many other things, a love of running together. Here they’ve just finished running from the south to north rim of the Grand Canyon. Photo Courtesy of Kathy Kusner.

“I thought, ‘Well, one of these racetrack girls will do it.’ There were girls at the track on the backside working that were light enough. Their whole life was that. I had this other life too with the United States Equestrian Team, sneaking away for short times to do whatever I could with race horses, so of course one of these girls would do it, and, well, of course they didn’t,” she says.

Four years passed.

“I was now 28 years old. I decided I had to give it a try because nobody else was doing it,” she explains.

“Saratoga was over, and I’m driving back to Maryland thinking how much fun I’d had galloping and breezing horses, sometimes alongside the great Hall of Fame jockey Angel Cordero Jr. It was just too much fun!” she recalls.

Kusner’s boyfriend at the time was the leading steeplechase and Hall of Fame jockey Joe Aitcheson. Joe’s first wife, Audrey Melbourne, was a lawyer. Audrey was Joe’s lawyer when he divorced his second wife.

Kusner told Melbourne she wanted to get a jock’s license and asked if she would consider being her lawyer. Kusner offered her savings of $1,500 if she would take the case, or at least start the case, realizing this wasn’t going to cover much of the legal fees. Melbourne said she would take the case pro bono because it was going to be a landmark ruling.

And it was.

“I just wanted to get a jock’s license,” she says. “This wasn’t a movement thing; I just wanted to ride races! I love the Civil Rights Act, not for my situation particularly, but for everybody. For all races and religions, etc.—all people.”

Homfeld again, “She has cared about injustice for as long as I have known her. It means something to her.”

She had to go three times before the Maryland Racing Commission only to be denied and told she wasn’t good enough.

“I had already ridden in two Olympic Games, but I couldn’t ride well enough to get a jock’s license. They would have rather died than give me or any girl a jock’s license,” she says.

Finally, Kusner and Melbourne took their case to court. It took the judge three minutes to grant Kusner her license.

The ruling garnered a lot of attention and press.

“I was dreading the press. They’d already been everywhere all the time, outside my house. I was walking the course at a horse show, and they came in there. I thought now that I had my license this is really going to be a big pain. I didn’t give any interviews, and I was going to have to tell a lot more people I didn’t give interviews. But it wasn’t too bad because not long after, I had a horse fall at Madison Square Garden and broke my leg and was in a cast for six months,” she says happily.

She used that time to study for her instrument written exam (flying).

Diane Crump and Barbara Jo Ruben would each get their licenses and become the first women to ride in recognized races. Crump was the first to ride in a sanctioned race, and Ruben was the first female jockey to ride a winner. Curious if Kusner felt disappointed she didn’t have that distinction she answers quickly, “No! They took away all the press. I was thrilled and thankful. I didn’t want to be the first one to ride; I just wanted to ride.”

And ride she did, at tracks in Peru, South Africa, Colombia, Rhodesia (present day Zimbabwe), Panama, Germany, Chile and Mexico City, finding more success on foreign soil.

Kathy Kusner is well known for becoming the first woman to receive a jockey’s license, but she wasn’t in it for the publicity. “I didn’t want to be the first one to ride; I just wanted to ride,” she said.

“I was their novelty. They had more people come out to see a girl ride. Their betting handle was higher than it ever had been at each of the places, so that was their reward, and my reward was getting to ride some live horses, much more than I could ever hope to get on in the U.S. Girl, no apprentice allowance (bug)! Why would anybody use me?” she says. “In other countries I rode some good horses, and that was so much fun because I had a shot.”

Asked if she had a preference for show jumping or racing, Kusner replies, “No. It’s like swimming and diving. They aren’t at all alike. There is water in both and horses in both, but that’s where it ends.”

As for the “good ole boys” in Maryland, they were forced to allow her to ride in the famous Maryland Hunt Cup, which she did in 1971.

“The night before the race, they tried to stop me. They never had a girl, and they didn’t want to have a girl ride in the Maryland Hunt Cup, but one of the members of the committee was a lawyer, Turney McKnight. He said I had my license, and they could not stop me,” she says. “Many girls have ridden since then and won the race, including Turney’s wife, Liz.”

Three Olympics

In addition to the 1964 and 1968 Olympic Games, Kusner represented the United States in Munich in 1972 as well as rode for two Pan American Games (São Paulo in 1963 and Winnipeg in 1967).

Ask Kusner about these experiences, and there are no boastful recollections of what it felt like to be on an Olympic team or how it felt to bring home a silver team medal from Munich or a gold from the Pan Am Games in Winnipeg.

It’s all about the people she met.

There were the boxers from Philadelphia she brought back to the U.S. barn, introducing them to the first horses they ever touched. Or the track and field contingent she would shadow during the opening ceremonies and around the Olympic Village. “I was a track spy,” she confesses.

“I was totally enchanted by the whole thing. The Olympics are so much fun; you can’t even stand it!” she shares.

The equestrian team always worked in the early morning hours. Upon returning to the Olympic Village Kusner would explore.

“When you are at the Olympics, there are big cafeterias. While in line, I would always ask, ‘What are you?’ to the person standing in front of me and behind me. In Tokyo in 1964 there was this great looking, tall guy in front me. He said, ‘I’m running the 10,000 and maybe the marathon.’ We both said we had no shot but how fantastic to have made the team and to be here. That’s sure how I felt,” she says.

This man in line would, in fact, have a shot in these Toyko Games. It was Billy Mills (who would later be the subject of the film Running Brave). Coming from behind the pack, he steadily made his way to the front, becoming the first American to win the Olympic 10,000 meters.

Kusner would later indulge her running obsession, competing in more than 120 marathons and 73 ultra-marathons (20 were over 50 miles) and the Vermont 100-mile Endurance Run (with a time of 27 hours and 37 minutes). Through this world she met competitive runner Craig Chambers, who became her life partner for the next 25 years until his untimely death from melanoma in 2008.

ADVERTISEMENT

Kathy Kusner competed in major grand prix classes and Nations Cup events all over the world. Here she’s shown aboard Old English in the 1972 Nations Cup at Lucerne (Switzerland). Findlay Davidson Photo.

An Eskimo

The lagoon and beach in Malibu thoroughly explored, we make our way to the next destination, sipping Diet Cokes from the stash Kusner keeps in her trunk. We arrive at a place she calls “heaven on earth,” a bucolic inner city park where she logs her daily miles, running up and down the winding dirt trails, past the ponds filled with turtles and a hummingbird garden with stunning views of the city, the Hollywood sign and surrounding mountains.

“I love the diversity of Los Angeles,” she comments as we stroll around, often stopping to chat with fellow park goers. “It’s everything. We have every kind of human.”

As if on cue, we notice a young girl standing next to what looks like a copper colored trophy. “We have to look,” she says, touching my arm, a gesture she has repeated throughout the day. It’s not a trophy but a hoverboard, tipped on the vertical. At Kusner’s urging, the girl gives a demonstration, smoothly gliding in circles, her braids clicking together as she spins. “You have to take a picture of this!” Kusner instructs me.

“To me, this is what is so much fun,” she confesses after we bid goodbye to the girl and her family. “Meeting all the people.”

At the urging of friend George Morris, Kusner began to give clinics on the West Coast in the late 1970s and decided to move to the area.

Morris says, “I’ve known Kathy for nearly 60 years. She has a little bit of a different personal life. She was very avant garde, and our lives paralleled each other. We enjoyed many of the same things outside of horses like the theater and arts. Kathy had her success, was very singleminded and tough, but she is also, as a person, very thoughtful and sympathetic to other people who don’t have advantages.”

“It was fun!” she exclaims, on giving clinics. “I didn’t expect that because I had never taught, but it was fun. I started doing more and more of them out here and really loved the area. I loved living in Maryland and had a life there that was great, but this does have a better winter.”

The day is warming up, and we both take off a layer. Walking down a trail, Kusner in front of me, I read the back of her T-shirt. “Nothing Stops a Bullet Like a Job,” a shirt from Homeboy Industries who participate in Horses In The Hood.

Kusner had always had the idea, since living in segregated Virginia, about introducing underprivileged children and people to horses. In 1992, with boyfriend Chambers, Kusner attended a play called “Watts Side Story,” put on by the 112th & Central Street School in Watts. Los Angeles was in chaos at the time, following riots. At the play, they met a teacher who told them he was going to be working with his students on a documentary about the riots and the children’s experiences and invited Kusner and Chambers to watch the process.

Also watching the hoopla at the school was a neighborhood “OG,” an original Blood gang member named Ronald “Kartoon” Antwine. He prefers to be called Kartoon, both in person and in print (and it must be Kartoon with a “K” because Cartoon with a “C” would align him with the Crip gang).

“I was on drugs and homeless,” shares Kartoon of that time in his life. “I am a lifelong resident of Watts, and I got caught up in the cocaine epidemic that came through our community. I took a shortcut through the school where they were making the documentary, and I stood right outside the film shoot.”

Unlike Chambers and Kusner, he wasn’t there to observe.

“I was looking for something to steal,” he confesses.

Kartoon noticed several walkie-talkies and chargers brought by the crew. “My mind was set on that, but it just so happened the guy they were interviewing was talking about my neighborhood, and everything he said was inaccurate,” he says.

After interrupting the interview several times, correcting mistakes, Kartoon was interviewed.

“There is nowhere she is afraid to go; there’s nobody she’s afraid to approach, and she is just so humble,” said Kartoon (left) of his friendship with Kathy Kusner. Photo courtesy of Kathy Kusner.

In the same place at the same time, Kusner did what she always does. She started talking to the man she simply calls “Toon,” and they became friendly.

“Craig was Kathy’s guy. They were inseparable. They come, and they start talking to me. The next day, I showed up, and they did too, and one thing led to another,” Kartoon says. “Kathy stayed in touch with me. She’d come out to Watts and track me down.”

By the time the film premiered, Toon was nowhere to be found. Asking around the neighborhood, Chambers and Kusner learned that he had been arrested for carrying a shotgun. This would not be his first visit to jail; he has served time in every penitentiary in the state, but it would be his last.

“Lo and behold, Kathy showed up at court. There she met my mother, and they became real good friends. Kathy would come to the jailhouse to visit me. This lady just wouldn’t leave me alone,” he says, chuckling at the memory.

Prior to meeting Kartoon, in fact since the 1960s when she went to her first meeting with Butler, Kusner became sold on AA. Since that time, she has gone to countless meetings with friends in the program.

“The result for so many people is unbelievable,” she says.

Kartoon explains, “She fell in love with the people who were once doomed, but now their life had been recreated. She’s fascinated by that.”

Kusner explains her lack of interest in alcohol: “It wasn’t because I was an athlete. I just have no interest in drinking or drugs or smoking. But I do go to a lot of meetings because it’s just the best thing for humans. End result? Happy people with great friends.”

One such person was Kartoon. He will mark 23 years of being clean and sober this year after Kusner and Chambers helped him find a recovery center upon his release from the 11 months he served in prison in Chino.

He has since earned a college degree and worked in recovery for a decade, helping countless others in his community get and stay sober, and he works as a location scout for films and TV. He also created Serenity Park in Watts across from his home (named for the Serenity Prayer spoken in AA meetings), an oasis of greenery and playgrounds where once the weeds grew taller than people, and crime was the only activity practiced there. The ripple effect of his sobriety is enormous.

“Kathy is just the greatest. In recovery, we talk about people who have helped us get on the roads of recovery. We call them our ‘Eskimos.’ That’s how we talk, in recovery language. Kathy is my Eskimo. With her personality, she can go into an all-black community, and they don’t look twice at her. They just look at her like this lady is for real. Just the spirit she has. Once you meet Kathy, you never forget her,” Kartoon says.

“Kathy and Craig always stayed by my side,” he adds. “They stayed with me for my first 12-step meeting, and that was 22 years ago. If it wasn’t for Kathy I’d probably be in prison now or dead or worse—I could still be trapped, using drugs and alcohol.”

The Serenity Prayer, a cornerstone of AA and CA meetings, seems to reflect the way Kusner lives her life. It reads: “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; courage to change the things I can; and wisdom to know the difference.”

Despite not being religious, (“They talk a lot about God in AA, but you can do with that as you chose,” she says) she sang in a gospel choir at The First AME Church for eight years. She liked the people, and they must have liked her too because she admits she really can’t sing.

For his part, Kartoon had no idea that his friend had such an illustrious past.

“Kathy has taught me the art of humility. She doesn’t go around saying she was in the Olympics or she was the first female jockey. She never told me. I read about it in some article and had to ask her if it was the same person. One of the greatest things Kathy told me was, ‘Kartoon, I would never give you any money, but I will teach you how to be self-sufficient.’ That was the great life lesson she taught me,” he says.

He pauses.

“When it comes to how I believe God would want everybody on earth to be, he would certainly use Kathy as an example,” he adds. “She doesn’t have a racist bone in her body. There is nowhere she is afraid to go; there’s nobody she’s afraid to approach, and she is just so humble. Humble.”

Spitfire, Finally

Before heading back to Kusner’s neighborhood, we stop at a marina where Kusner charms the attendant into letting us on the bait dock, past the “prohibited” sign, to look for sea lions. We pass a boat, the name Spitfire scrolled along the stern. We’ve finally found it! OK, so maybe it’s not an airplane, but we laugh all the same.

Kusner lives in Playa Vista, a planned community built on the former site of the Hughes Aircraft Company. The enormous hangar that housed the world’s biggest airplane, The Spruce Goose, still stands and is now used as a sound stage.

It makes sense she lives here. The aviation connection but more importantly, the variety of people she calls neighbors. Despite her affinity for children, Kusner never wanted her own or to marry.

Kathy Kusner won classes all over Europe, including at Aachen (Germany) in 1972, aboard Nirvana. Pressebild Guido Wedding Photo

“That I never wanted to do,” she says.

Another longtime friend, Bill Steinkraus, shares, “She’s lived her life on her own terms and made her own choices. She’s lived a very individual life, and it’s all been through choice.”

After watching the children in the park and marveling in the variety of faces, we stop by her condo where I am greeted by life-sized cutouts of Barack and Michelle Obama, reminders of how much has changed in her 76 years.

Her walls are covered with photos and mementos, prints of birds, framed chunks of the Berlin Wall she and Chambers tore down on one of their many trips around the world, a framed poster of Nelson Mandela, a framed print of Norman Rockwell’s iconic Civil Rights Movement painting The Problem We All Live With, and a never-published photo of Charles Lindbergh the day after he landed at Le Bourget in France.

I ask if the fit, tall man beaming back from many, many photos is Craig. “Everything is Craig,” she says softly. His presence fills her home.

Kartoon will later tell me, “Craig was her shadow. I really thought she was going to lose it when he passed. She does everything to honor his memory. He was another one that defines humility.”

“We called him ‘The Moose,’ ” Kusner explains, standing in front of a photo of herself and Chambers, both smiling after running from the south rim of the Grand Canyon to the north. Ten times, Chambers would run back. This is known as “the double,” and Kusner joined him twice for a round trip total of 46 miles. Kusner also did approximately 13 single crossings from the south rim to the north rim.

In addition, Chambers ran the Hawaii Ironman, three Western States 100 Endurance Runs and a Death Valley ultra triathlon consisting of over 200 miles of biking, 10 miles of swimming and over 100 miles of running. As well as more than 200 national and international marathons and ultra marathons.

“He used to run to work and back for five years, and it was a 26-mile roundtrip. He was part owner of a running store on the other side of the mountain and was a big reader. He always had a backpack with books. A pack moose. The Moose. His death was really…” she pauses before concluding simply, “Sad. He was so terrific. He was interested and smart.”

Her home, the art on the walls, the snapshots with Chambers, feels celebratory. What I don’t see are framed photos of Kusner riding or at any of the Games. Currently, in addition to some training and her work with Horses In The Hood, since 1983 Kusner has been employed as a horse expert witness for horse-related cases. She was introduced to this work by her good friend, Frank Chapot.

It is now 12 hours after we began our day at the Spitfire Grill, and Kusner drives me back to my hotel. Her parting words to me as I turn around for one last wave, “Remember, make it bland!”

Now, I love a challenge, but that is asking the impossible.