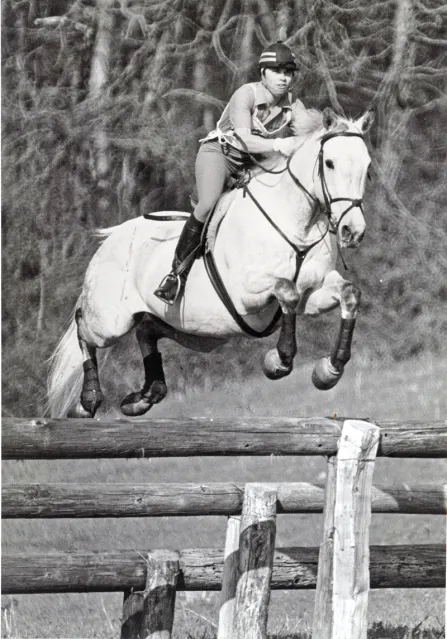

With her Irish-bred gelding, Kim Walnes won Rolex Kentucky and two World Championship medals in 1982.

Exactly 30 years ago Kim Walnes was living a fairytale. It was June of 1982, and the mother of two young children, a woman whom no one in the then-small circle of upper-level East Coast eventing had even known three years before, won the Rolex Kentucky Three-Day Event on a long-backed gray gelding she’d bought in Ireland and trained by herself.

And just three months later, she and The Gray Goose would add a second chapter to their fairytale, earning the individual and team bronze medals at the World Three-Day Championships in Luhmühlen, Germany.

“ ‘Gray’ just loved Rolex and the Kentucky Horse Park. That was his spot. He loved the turf, he loved the wide-openness of it, he loved the big fences—he just loved the challenge of it,” said Walnes, who first rode Gray at Rolex Kentucky in 1979 and last rode him there in 1985.

“It was one of the most thrilling cross-country rides of my life. It was amazing—we were so in sync, with such a beautiful rhythm and flow,” she added, fondly remembering the 1982 victory. “It was one of the best cross-country rides ever. I don’t remember a single bad step. We were really one unit, going for a common goal and loving every second of it. It was just joyous.”

The Gray Goose officially retired from competition at Rolex Kentucky in 1988, and his ashes were, fittingly, buried at the Kentucky Horse Park after he died in June 2000.

Gentle—Unless He Was Frightened

Life with Gray wasn’t always joyous, though. It could be frightening, even dangerous, at times. He was quite clumsy as a young horse, and certain things in his environment, like fog, could completely un-nerve him, causing him to buck and bolt, whether he was being hand-walked or ridden.

“He was a very sweet, gentle horse—unless he was frightened. And then he would mow you down without a second thought,” said Walnes, 64. “You just had to know that about him. If you were standing between him and what he perceived as freedom, and something was after him, he would just run you over. At any other time, he was the best-mannered horse in the barn.”

Walnes first saw Gray when he was 3, at a foxhunting stable in Ireland, where she and her then husband, Jack, lived in the mid-’70s. But their relationship didn’t really start then, because Gray injured both knees while hunting, and Walnes suffered a back injury that forced her to return to the United States for a time.

| Clumsy And Graceful—Like A Goose When he was a young horse, The Gray Goose didn’t exactly look like a future eventing star.He was gangly and an awkward mover—something less than grace in motion.To overcome this, for the first several years she rode him, Kim Walnes spent hours walking Gray up and down steep or rocky hillsides, first in Ireland and then in southwest Virginia, teaching him to pick his own way through the terrain and to rely on himself, not on her. “That’s the reason he got his name—because geese aren’t very graceful on the ground, but when they fly, they are,” said Walnes. “I decided to call him The Gray Goose because he was poetry in flight, when he was galloping, but clumsy on the ground.” |

When she went back to Ireland, Walnes asked if she could take Gray on as her project, even though he was throwing just about everyone who tried to ride him. After some challenging months of being bucked off or run away with, Walnes bought him and a mare by the same stallion, and she brought both horses with her when she, Jack and their daughter Andrea, then 4, moved to southwest Virginia in the summer of 1976. Their son, Brian, was born in 1977.

Walnes recalled that Gray was almost black when she first saw him, with a bump between his squinting eyes. “He reminded me so much of another horse that I’d had, who looked exactly like that,” said Walnes. “My bond—not his—was right there from the get-go.”

Gray was terrified of much of the world around him: other horses jumping, indoor arenas, even the high-pitched rattle that Volkswagen Beetles used to make. Walnes recalled that, on a foggy morning shortly after they’d moved to Virginia, Gray jumped out of his paddock in a panic, over the slanted roof of a shed, because people were standing in front of the gate that he really wanted to jump. They measured the shed he’d jumped at about 8’6″ high.

Despite the challenges of Gray’s temperament, Walnes persevered with him because she knew he could jump and gallop. “I figured some things out. He really helped me understand that he was a horse who became aggressive when he was frightened—and he was terrified of everything. That appealed to me to win him over, to try to help him gain confidence. I had to start thinking way outside the box,” she said.

“There was something that kept driving me forward. He was an enigma, and he wanted me to sort him out,” she recalled. “And then, as he began to get better, I began to think about my dream to be on the [U.S.] team—that had been my dream all my life.”

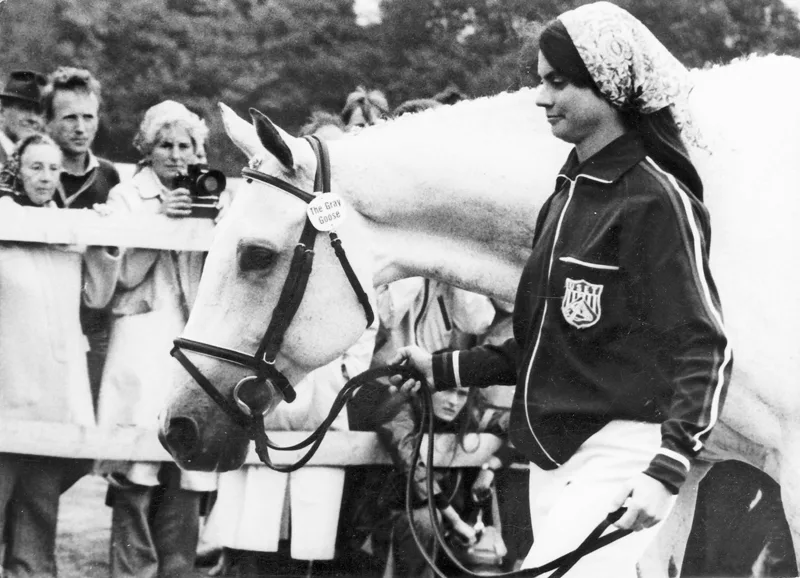

Kim Walnes and The Gray Goose at the Luhmühlen World Championships horse inspection in 1982. Photo by Hugo Czerny

Walnes had no trainer in the hills of southwest Virginia, so she read all the books she could find about dressage and jumping. She would usually read a page while sitting on Gray, then prop the book up on the fence and try to do what the author instructed.

“I’ll Be Back Here Next Year”

Like so many future eventing stars, Walnes felt a tremendous inspiration from the 1978 World Three-Day Event Championships, at the new Kentucky Horse Park. She and her husband went there to watch, and she walked around the imposing course.

“My wheels were turning the whole time, and I said to Jack, ‘I’ll be back here next year.’ He just looked at me, and I said, ‘There isn’t one jump out here that Gray can’t jump. We don’t have the conditioning and the experience right now to jump them all together this year, but by next year we will,’ ” she remembered.

And she was right—in 1979, the first year of what would quickly become America’s biggest event, Walnes and Gray finished second to Torrance Watkins in the intermediate division at Rolex Kentucky.

“It was the thrill of a lifetime—so far. We did it ourselves—I didn’t have anybody to help me, except for Jack,” she said.

As a result of that finish, Walnes got a letter from the U.S. Equestrian Team inviting her to her first training session with coach Jack Le Goff. Le Goff, who died in 2009, once said of Walnes and Gray, “I think the reason for their success is that they got together quite early on, and she has done everything with him. It’s just like if you have a dog and you are the only master he knows—he gets used to you and only follows you around.”

Spectators always enjoyed listening to Walnes talk Gray around cross-country courses, warning him that there was a ditch in front of the next fence, or that the water complex was coming up, or that he needed to slow down. His ears would prick back and forth, and he would swish his tail in apparent agreement.

ADVERTISEMENT

| Their Bond Of Trust Anyone who ever watched The Gray Goose and Kim Walnes gallop around a cross-country course or perform a dressage test could tell they had a special relationship, a bond of great communication and trust.“I’m sure destiny played a part. I think we were meant for one another,” said Walnes. But she believes that their relationship was more than just a lucky twist of fate. “I think that I was willing to listen to him,” she said. “All the humans he’d met, up to that point, were just interested in making him do something he didn’t want to do. He wasn’t happy inside his skin, and I was willing to listen to him and work with him.”For instance, “I was told I had to keep him round when he galloped, and I thought, ‘I can’t do that with this horse, that’s not his style.’ He needed to run and jump his way—why mess with a good thing? The horse was a cross-country machine. Why would I try to change that? “I think that, because I wasn’t trained, and I didn’t know the ‘right way’ to do things, we just did it our way, and I listened to him a lot,” she added. “Out of that grew respect. And out of respect started to come trust and love. It was that love that turned his fear into trust.” Walnes, who’s lived in Milford Square, Pa., since 1995, said that the list of things Gray taught her is just about endless. She hopes to write a book about their experiences, many of which she describes on her website www.thewayofthehorse.com. “I use so many things he taught me about listening to our horses,” said Walnes. She added, “I used to think Gray was unintelligent, that he didn’t have enough brains to figure things out. But as I began to work with people who approached horses differently, like Linda Tellington-Jones and Sally Swift, then his intelligence began to develop. Looking back, it wasn’t he who didn’t have enough intelligence; it was me not understanding him. I had to open my mind to understand him.” |

“I personally have had a lot of fun listening to them,” said Le Goff in a 1986 Chronicle interview. “If you could have put a tape recorder on her saddle, you would have the whole story, because she talks to him all the way around. I’m not sure if it’s for her or for the horse, but it works.”

Walnes and Gray would place again, this time in the advanced division, at Rolex Kentucky, in 1980 and 1981. And in both years their performances would earn them a slot on the U.S. teams Le Goff took to the Luhmühlen CCI in preparation for the 1982 World Championships there. Gray would jump faultlessly around Luhmühlen’s cross-country course both years, but tense and stiff dressage tests and dropped rails in show jumping would keep them from placing. Still, those starts at Rolex Kentucky and at Luhmühlen provided her and her horse with the experience they would need in 1982.

Victory At Rolex Kentucky

With the 1982 Rolex Kentucky Three-Day Event on the horizon, Walnes told Le Goff, “I really need to up my game, to understand the science behind what makes a good dressage test and a good show jumping round.”

By then, the Walnes family had moved to Connecticut, so she started working with dressage trainer Pam Goodrich three days a week and working with a local show jumping trainer another one or two days a week. “By the time the spring season came around, I was a different rider,” said Walnes.

Gray won the Ship’s Quarters (Md.) event and was third in another start prior to Rolex Kentucky. “I wanted to win Rolex—I went there with the goal to win,” she said. They placed a close third in dressage, even though Walnes’ new top hat, which had arrived that morning, didn’t fit, causing it to ride up her head throughout the test. But it didn’t fall off, because she’d attached it to her hairnet.

Before the start of cross-country, she had to overcome something that every rider fears at a three-day event: being late for the start. Walnes recalls that someone lost track of the time in the 10-minute box, “and I started at least 10 seconds late, so I had to go out there on fire and keep on fire. Gray said, ‘Really, you’re not going to rate me? I can really run?’ ” The result was an unforgettable round that put them in first place.

Their top placing meant that they would be the last to show jump, a brand-new experience on a hot and humid afternoon. Still, they kept all the rails in place to earn the blue ribbon and the Rolex watch.

“It was one of the happiest moments of my life—having my children and winning Rolex were both amazing, just amazing,” she said. “What I remember most is the gratitude and the thrill, that Gray was willing to listen—when his answer always used to be ‘No’—and he tried so hard. And my team—my groom, and the folks who traveled to help me out, and my family. All that hard work that we had put in had paid the ultimate dividend. My hopes and dreams came true, and it was an amazing feeling.

“And Gray was as proud as he could be,” Walnes added. “He was so happy to lead that victory gallop. It was a beautiful day. And I didn’t care about how hot it was at that point!”

Rolex Kentucky was the final selection trial for the World Championships, and now Walnes’ sights shifted to Germany. But a fall six weeks before the early September event nearly ended the fairytale.

Dream To Nightmare

Walnes fell off during a show jumping school with Le Goff, when Gray shied at a shadow in the middle of a combination. Walnes landed with her back against a jump standard and broke two transverse processes.

“Now the dream had become a nightmare—all of a sudden it could just be nothing,” Walnes recalled. “It was pretty brutal—I had to stay fit, and the only thing I could do was walk, and I walked hours and hours every day.”

Frustratingly slowly, Walnes began to heal, while watching her teammates train in France, Mike Plumb riding Gray while she couldn’t. When she finally did get on Gray again, about a week before the championships, she thought Gray seemed relieved, glad to have her back and determined not to lose her again. They did a cross-country school and a dressage school, and then the horses shipped from France to northern Germany, with Walnes and Gray slated to be the team’s anchor pair.

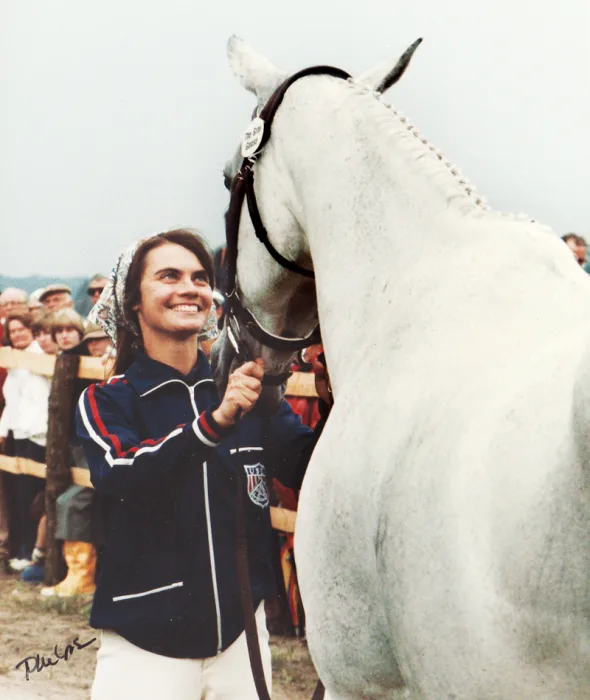

Kim Walnes and The Gray Goose at the first horse inspection of the World Championships at Luhmühlen in 1982. Photo by Mary Phelps

“In dressage I took a chance. He was terrified of the red geraniums that surrounded the letters. When I warmed him up for the dressage, he was calm and peaceful and supple, but that doesn’t necessarily give you a winning dressage test. You need a little fire. So I got as close as I could to those red geraniums when I cantered in at A, and that upness lasted for the whole test—we were second,” said Walnes. “It was the best dressage test we’d ever done.”

Walnes said her back felt fine as she and Gray completed phases A, B and C before the cross-country course. And it stayed fine until a combination of two giant tables, a bit more than halfway around the 13-minute course.

“He made a big effort over the first one, and then he really had to launch over the second one, and when I went with him in midair to really let him stretch, those bones separated again,” said Walnes.

ADVERTISEMENT

“When we landed, I didn’t have my left leg. The whole left side of my body was weak, so there was no way I could pull on the left rein to help him or to balance him. All I could do was hang on to his mane and stay wrapped around him as best I could, and direct him with my body and my eyes. There was nothing else I could do.”

The second-last fence was a demanding water complex, truly a final test. “I knew there was no way I could help Gray through that water, and I didn’t want him to be too tired when we got there. So I took all the shortest routes between the jumps as we headed toward that water complex, and he followed my eye over every little thing—and then we got through that water,” said Walnes.

“We did it, we’d made it around without jumping penalties, but I had some time penalties, so we were in second. If I’d gone clean, we would have been in first.”

But the championships weren’t over. “The next day was just a nightmare. The pain was really bad, and I had to get through show jumping,” she said.

She returned to her walking routine to try to stay loose and then completed show jumping with just one rail down. If Gray had jumped faultlessly, they would have won the individual silver medal, but the team wouldn’t have moved up from the bronze-medal spot.

“I give all the credit to my horse and to the partnership that we’d created, that he would follow my eye and go over anything I looked at. We’d been through so much together that I could just hold his mane through the second half of a World Championship course,” she said. “By that time, we truly trusted our lives to one another, and he came through for me.”

Kim Walnes and The Gray Goose with their bronze medal from 1982 World Championships at Luhmühlen. Photo by Mary Phelps

Concussions

Although they’d compete at advanced for another four years, 1982 would mark the highpoint of their career. In May 1983, Walnes and Gray joined the U.S. contingent at the Badminton CCI (England), but a horrifying fall at a stone wall set at the bottom of a muddy hill put them on the sidelines for the rest of the year. Walnes said Gray slipped and stepped on his left front hoof at take-off, causing him to flip, since he couldn’t get the leg up in time to clear the jump.

“We both had concussions, and it took awhile for our confidence to come back, but it did,” she said.

In the Olympic year of 1984, Walnes and Gray suffered a refusal at the second of the three selection trials and were left off the gold-medal team. Instead, they served as the stunt doubles in the movie Sylvester, filmed at the Kentucky Horse Park.

But strong performances in 1985 earned them a place on the 1986 World Championship team, which left for the May competition in Gawler, Australia, before the U.S. spring season had begun. Gray placed in the top 10 in dressage, suggesting that there was still another chapter to be written in the fairy tale.

Two factors would weigh heavily against Gray, now 16, in Australia, though. The first was that, after a six-month drought, the heavens opened up as the championships got underway, creating a soup covering the hard-packed footing, with almost no grass. “It was like an ice-skating rink,” said Walnes.

Second, this was a decade before FEI officials acknowledged that women now made up more than half the riders in their events and that the rule requiring horses to carry a minimum of 165 pounds in the jumping phases placed their horses at high risk. Walnes had to strap an extra 25 pounds of lead to her saddle to make 165 pounds, and at every three-day event Gray would lose his right front shoe jumping into a water jump. It was the only time he regularly lost that shoe, and Walnes suspects that the extra weight made him unable to get that foot out of the way when he dropped into water.

Early in the course, Gray slipped in front of an oxer and touched down on it with his hind feet to bank off it. The trailer on his left hind foot caught on the jump, forcing him to kick out of the shoe. And then he pulled his right front shoe off at the first water complex, meaning he was now missing diagonal shoes, and it was still early in the course.

Walnes was riding as an individual, not a team member, this time, and she tried to pull Gray up “because he didn’t feel in balance or in control.” But “I heard a voice in my head saying, ‘If you pull me up, I will die of failure and humiliation. I need to keep going.’ So we kind of hunted around the course—going slowly and taking the easier options. We came through the finish line, and he was so happy. But 10 minutes later he was lame in his feet, so we withdrew,” said Walnes. “That was my reward to him for all those years—to trust him to take care of us.”

Gray would run one more time, just under a year later, finishing third at Ship’s Quarters. “But he wasn’t himself,” said Walnes. “He was just bored. He knew these courses inside and out, and I said, ‘I think we’ve done enough.’ ”

The Gray Goose died on June 17, 2000, of an apparent stroke at age 30. His ashes were buried above the Kentucky Horse Park’s Head of the Lake, in a gravesite he shares with Volturno and Le Samurai, a gravesite that the Kentucky organizers decorate with flowers every year for the big event.

Hallowed Ground

Even if The Gray Goose hadn’t won the Rolex Kentucky Three-Day Event in 1982 and his gravesite didn’t overlook the Head of the Lake, the Kentucky Horse Park would still be a special place for Kim Walnes.

“Ever since I first set foot on the Kentucky Horse Park for the 1978 World Championships, it has felt like hallowed ground to me,” she said. “There is something about the feel of the place—the age of it, the trees, and the way the ground lies. It has an ageless peace about it. Somehow, and I know this sounds odd, but somehow it just always felt like ‘home.’ ”

Walnes was sure in September 1978 that she would ride The Gray Goose in what the next year became the Rolex Kentucky Three-Day Event.

“Right then and there I decided that I would come back and do that course,” she said. “And if ever there was one competition I would want to win, it would be that one. Galloping on that wide-open turf (there were no galloping lanes back then), feeling your horse fly over that undulating steeplechase course of perfect footing, meeting those incredible obstacles on the right pace in perfect harmony with your equine partner—that’s the stuff dreams are made of. And jumping that last stadium fence cleanly to win—there are no words for that, only a heart full of gratitude, awe and bliss.”

This article ran in the April 23, 2012 issue of The Chronicle of the Horse, the annual Rolex Kentucky Preview Issue. For more stories like these, make sure to subscribe to The Chronicle of the Horse.