The Chronicle of the Horse is celebrating its 85th birthday in 2022. For eight weeks leading up to the publication of our 85th Anniversary Issue, we’re bringing you a decade-by-decade look at the history that has filled its pages since 1937.

In a July 29, 1988, commentary, editor John Strassburger took stock of the last eight years in horse sport, marveling at the expansion at the top levels of the sport:

“Prize money in show jumping has quadrupled; the show hunter and equitation world has become an industry in which people actually make a good living selling and training; and dressage, combined training, driving and steeplechasing all have more competitors and events. And in each sport the price of good horses has become even dearer, even unbelievable.”

For better or worse, during the 1980s, the culture of the horse world was modernizing, becoming more specialized and more of a business, less bound by tradition. The show hunter that got its start in the hunt field was now very much a minority, and money, as they say, was starting to talk.

Rodney Jenkins signed autographs after finishing second in the Chrysler I Love New York Grand Prix in July 1988. Ellen Wiese Photo

Twenty-four years before setting records by purchasing Moorlands Totilas, Paul Schockemöhle paid a shocking amount—$1,025,000—for top Irish horse True Blue (whom Trevor Coyle rode to double clear in Nations Cup competition in Aachen, Germany). He sold the horse a week later for Swiss rider Willi Melliger to ride, temporarily derailing Irish plans to send an Olympic team to the upcoming 1988 Seoul Olympic Games.

In 1989, the National Horse Show left its home of 105 years at Madison Square Garden in New York City and moved to the Meadowlands at East Rutherford, New Jersey.

The modern age also ushered in more oversight as well, often with the intention of protecting the horses in meaningful ways. Proper conditioning became a much discussed topic from Pony Club to top event riders, as increased visibility in the sports meant there’s more attention when accidents occur.

And the American Horse Shows Association stepped in to try to seriously address horse welfare concerns, from limiting permissible amounts of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to empowering stewards to addressing how to keep horses from being over campaigned in the quest for year-end awards.

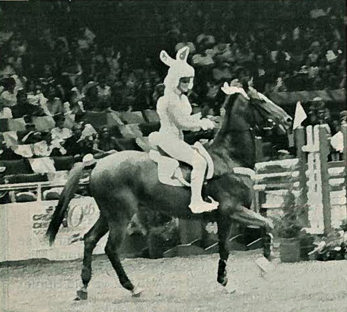

Anne “Kurbunny” Kursinski played the March Hare to Jay Land’s Mad Hatter in the Fancy Dress Relay at the 1984 Washington International (Md.). Photo by Detailer

This Just In

At the Chronicle, Peter Winants ushered in the decade as the editor, with Strassburger taking over in 1986. But Winants stayed on as president, and editor emeritus Alexander Mackay-Smith still shared his considerable expertise, writing occasional reports on hounds. Horsemen like Denny Emerson, Michael Poulin and Judy Richter become regular columnists by the end of the decade, and Cooky McClung’s distinct brand of humor earned legions of fans.

The magazine reported on combined training, dressage, jumpers, show hunters, foxhunting, hound shows, driving, polo, endurance, steeplechasing, flat racing, para-equestrian, Pony Club and vaulting. During the 1980s, the magazine’s focus shifted to more analysis of the Olympic sports, with plenty of homage to hunt country roots. But by the end of the decade, polo and flat racing were, at best, afterthoughts.

Signs Of The Times

Imported warmbloods proved they weren’t a passing fad but a growing trend, with ads from Hanoverian and Holsteiner studs popping up more and more. (The Trakehener, by and large, had already blazed the trail for his fellow imports.) But the American Thoroughbreds, as they were often referred to, were still the most popular.

Charlie Weaver continued to dominate the hunter divisions throughout the 1980s, shown here winning the regular working title at Rosemont Farm (Va.) on Up My Sleeve for Cismont Manor and A. Busch. Judy Buck Photo

Issues of the day included the mileage rule, point chasing, the inability to find non-skin tight breeches (“At home my husband can keep me on an eternal diet by merely mentioning two magic words as I stand poised before the refrigerator door—“stretch breeches,” wrote Letitia Savage), whether to implement a national head-to-head dressage championship, whether the newly developed Maclay Regionals were a good idea, how to best encourage and improve the slumping hunter breeding division, and the alarming trend of riders counting strides. (Sallie Sexton said of the “stride fetish” in the pony hunter ring that, “Judges started this nonsense of taking X number of strides, or else.”)

Olympic Pride

The United States opted out of the 1980 Moscow Olympics and instead sent dressage, jumping and eventing teams to Europe to compete in festivals against other nations also sitting out the Games.

Melanie Smith and Calypso starred by winning individual show jumping bronze at the alternate Olympics. That pair returned to the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics (the first time the Games had been on U.S. soil in 52 years), which West German show jumping anchor Schockemöhle, summed up neatly: “The Americans made us look like fools. They were so good today it was impossible to beat them.”

In a script worthy of pitching to a nearby Hollywood studio, U.S. riders Smith, Joe Fargis, Leslie Burr and Conrad Holmfeld, coached by Frank Chapot, trounced the courses set by their former coach Bertalan de Nemethy to win team gold for the first time in history. Fargis and the inimitable mare Touch of Class won a gold-medal jump-off against his friend and teammate Homfeld on Abdullah. The domination prompted letters of congratulation mailed to the Chronicle from around the world, and the Southampton, New York, mayor to declare Aug. 29 “Touch of Class Day.”

Show jumpers earned team silver in the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games as well, when Greg Best put in the strongest performance to score individual silver on Gem Twist.

Greg Best scored the first grand prix win of his career aboard Gem Twist, and that pair went on to win individual and team gold at the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games. Judy Buck Photo

U.S. eventers in Los Angeles wore team gold too, anchored by individual silver medalist Karen Stives and Ben Arthur. Legendary coach Jack Le Goff retired at the end of that year, and eventers couldn’t produce the same results in Seoul, where the team was eliminated. (Phyllis Dawson and Albany II were the lone bright spot, finishing 10th.)

ADVERTISEMENT

But the most memorable combined training medal went to Kiwi Mark Todd, who rode Charisma to back-to-back individual gold medals in ’84 and ’88.

The star of the ’76 dressage team, Keen, spent years out of commission with back and leg problems, but the Thoroughbred earned the highest U.S. score in Los Angeles with Hilda Gurney. Dressage star Robert Dover attended both Games, scoring the highest U.S. marks in ’88 aboard Federleicht, but the team wasn’t yet competitive against the dominant German squad.

Selection Gets Ugly

There’s always been consternation over the Olympic Selection process, but in 1988 it got ugly.

That year Kerry Millikin filed a complaint against the U.S. Equestrian Team and the American Horse Shows Association, arguing that the selection committee hadn’t followed the written criteria sent to long-listed riders. (The memo in question stated that, “All Olympic candidates must, in principle, have completed the [Kentucky CCI].”)

Millikin looked like a strong candidate to head to Korea after winning the Kentucky and Almaden Chesterland (Pennsylvania) CCIs in 1987 as well as the last Olympic selection trial at Fair Hill (Maryland). She broke her leg the following year at Kentucky on cross-country on HMS Dash and was unable to complete the event on Pirate, her Olympic contender, and she wasn’t included on the USET’s list for the Olympic squad or list of alternates.

While there was plenty of confusion over the timeline of the U.S. Olympic Committee’s approval of the selection process, arbitrator William M. DeLong eventually decided that Millikin shouldn’t make the list.

The pro- and anti-Millikin camps hashed out their opinions in the letters section of the magazine (as of July 1, 1988, the Chronicle received 64 letters against Millikin’s attempt to make the team, and 10 letters in favor).

And in show jumping land, Peter Leone followed suit after Millikin’s case was decided, arguing that he and Oxo should replace Katharine Burdsall and The Natural on the squad thanks to a superior record at the Olympic observation trials. But 24 hours before the USET had to declare its nominations for the Seoul Olympics, the arbitrator decided to let the USET’s announced team stand.

Occasional cartoons satirized issues in the sport, such as this one referencing the kerfuffle over the selection trials for the 1988 Olympic Games.

USET’s executive vice president John Fritz quoted USET President Vincent Murphy’s remarks in the Newark Star-Ledger (New Jersey): “These cases point [out] the difficulties of communicating how the Selection Committee is going to judge performance versus what the participants understand. That leads us to realize we must be far more clear in our explanations of the criteria and what we are looking for.”

Show Jumping Stars

While the ’70s seemed to be the golden years of U.S. eventing, in the ‘80s U.S. show jumpers ruled.

U.S. riders and our neighbors to the north won every single FEI World Cup Final in the 1980s, and some years Europeans didn’t factor at all in the medals. (Don’t feel too bad—Germans had a similar streak of good fortune through the 2000s.)

Conrad Homfeld and Balbuco kicked off a serious U.S. winning streak in 1980, followed by Michael Matz (Jet Run), Smith (Calypso) and Norman Dello Joio (I Love You). Canadian-turned-U.S. rider Mario Deslauriers, then 19, interrupted the U.S. onslaught in 1984 in Gothenburg, Sweden, aboard Aramis, but then the U.S. got back to business.

Homfeld rode Abdullah to win in 1985, Leslie Burr Lenehan (McLain) took the title in 1986, and in 1987 Burdsall and The Natural would become the last U.S. pair to win the award until 2012. Canadians Ian Millar and Big Ben picked up the torch, winning back-to-back titles in 1988 and 1989.

The U.S. team of (from left) Norman Dello Joio and Allegro, Katie Monahan and Silver Exchange, Melanie Smith and Calypso and Armand Leone and Encore enjoyed a victory lap at the 1980 Dublin Horse Show after winning the Nations Cup. M. Ansell Photo

After coaching the U.S. team to win at the Prix de Nations at the 1988 CSIO Spruce Meadows Masters (Alberta), George Morris rode Rio to the biggest purse in show jumping history to that point when he won the $506,000 du Maurier International Grand Prix at that show.

“Watch out for old horsemen,” he said. “Horsemen of the old school learned a lot out of necessity—you had to do more for yourself. We rode our horses to the shows—you fended for yourself. Young kids today have a disadvantage because it is too easy.”

In the 1980s, even the up-and-comers looked good. “The article on [Chris] Kappler in the Feb. 21 issue was an interesting description of a very good young horseman,” wrote reader Judith Moore in 1986 in the letters section. “One comment though—Meredith Michaels of California has matched Kappler’s achievements in competing in equitation finals and the USET Finals—West.”

Right she was, of course, and the Chronicle gave Michaels her due when she won USET—West later that year (and in many future issues).

In The Galloping Lanes

At the 1980 Kentucky Three-Day Event, “a diminutive rider on a small pinto … grabbed the hearts and cheers of the Lexington crowd,” donning Pinto Power T-shirts in support of the eventual winners of the modified advanced division, Torrance Watkins and Poltroon.

ADVERTISEMENT

Poltroon would win individual bronze in 1980 at the Fontainebleau Three-Day Festival CCIO (France), which served as the alternative Olympic Games. While Jimmy Wofford and Carawich won individual silver there as well, the United States fell out of medal contention when the rest of the team failed to finish.

By 1981, the United States had its first CCI, at Chesterland (Pennsylvania), with Rolex Kentucky joining the ranks the next year. (In 1984 the Chronicle was still explaining what this new “CCI” designation meant to readers.) The last horse ran around Chesterland in 1988; by the next year the Fair Hill CCI (Maryland) gave riders a fall goal.

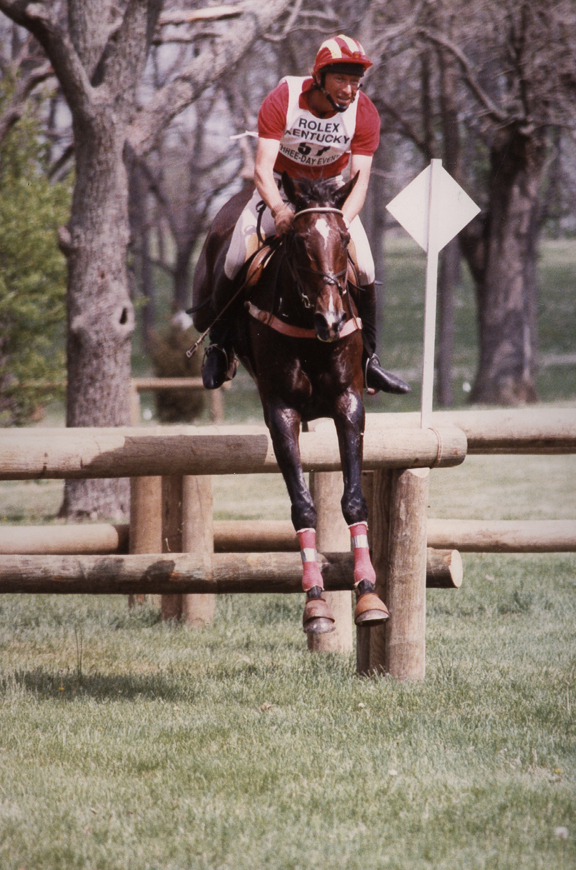

Bruce Davidson won the Rolex Kentucky Three-Day Event four times in the 1980s, three times aboard Dr. Peaches (pictured.) John Strassburger Photo

One name ruled the Rolex Kentucky leaderboard throughout the 1980s: Bruce Davidson. He won in ’83 with J.J. Babu and in ’84, ’88 and ’89 with Dr. Peaches. Wofford took a turn in ’81, retiring from competition shortly after he won for the second time with The Optimist in 1986 to work in governance, becoming president of the AHSA in 1989.

In 1988, Rolex Kentucky was a tough course. In response to hue and cry that U.S. riders needed tougher courses at home to be competitive abroad, Patrick Lynch upped the ante, with 14 falls, 10 retirements and four eliminations to show for it. (“This makes Badminton (England) look easy,” said Watkins.) Coupled with disappointment over the Olympic selection process, most combinations left the park with a bad taste in their mouths.

Strassburger summed up the morose mood, saying, “It seemed like a good idea, but now that it’s been done, perhaps it’s time to admit we cannot have a Badminton or Burghley (England) in this country. Leave the huge courses to the English and their perfect footing and climate. We don’t have enough horses or riders or owners or sponsors to sacrifice more every year.”

Horse Show Land

In the 1980s, the fall indoor circuit kicked off in Maryland with the Baltimore Jumping Classic.

In a 1984 state-of-the-sport interview, Victor Hugo-Vidal lamented that the hunters on the East Coast were lighter than in years past, and that equitation riders were doing less homework and learning on the road. (On the plus side, he said, the crest release was out of fashion.) Hugo-Vidal supported the growing number and popularity of the adult amateur divisions saying, “If that keeps up, and the adult amateur divisions encourage people to show, I’d even like to see an over-40 division. If you love the sport, you don’t stop loving it just because you grow older.”

After ages of grumbling about chasing points in an effort to earn Horse of the Year awards, the American Horse Shows Association trotted out the Increment System for the 1987 season, which had been years in the making. At the 1986 Annual Meeting, the chart received mixed reviews. (“A positive step forward. Let’s get on with it,” said Jim Green of Tennessee; “We’re against it, period,” said Gary Baker of Maryland.)

The Chronicle received plenty of letters opposed to the proposal, but the AHSA’s public relations spokeswoman, Kathy Fallon, said the majority of petitions the Association received favored the proposal. Whatever the initial reaction, the decision ushered in decades of disagreement over whether that system awarded points equitably, starting the year after it was passed.

Children’s hunter championship photos were becoming regulars in the show results alongside those from other divisions, and AHSA Pony Finals was a growing event, gaining momentum as riders like Laura Chapot and Marley Goodman get their first championship wins of their career under their belt. (One dispatch from the 1984 event described a 102-pony victory gallop!)

Dressage

During the 1980s dressage grew from the third to second most popular discipline behind hunter/jumper. The decade started with 8,000 U.S. Dressage Federation members and 61 Group Member Organizations (up from fewer than 3,000 members and 28 GMOs when the organization started seven years prior). By 1988 they had more than 22,500 members.

Robert Dover starred in the U.S. dressage scene in the 1980s aboard mounts like Romantico. Susan Sexton Photo

The base of the sport grew the fastest, but the standard at the top trended upward. The mean score for the 12 horses at the selection trials before the 1984 Games was a 59.55% in the Grand Prix and 60.14% in the Grand Prix Special, and by 1988 the averages were 61.32 and 62.32%, still far off the likes of the king of the sport Reiner Klimke.

Corinne Fentress Gray attended the International Dressage Festival in Goodwood, Sussex (Great Britain)—the 1980 alternative Olympics—to watch her daughter Lendon. She reported for the Chronicle with the cheeriest news for the folks back home being that U.S.-bred Turmalin and Swiss rider Christine Stuckelbuerger won the Prix St. Georges.

While the United States wasn’t internationally competitive in dressage in the ’80s, there were stars. Carol Lavell and Gifted graduated through the levels, starting by scoring 80% at second level at the York (Pennsylvania) IEO show in 1985 and earning Horse of the Year awards every year for the next four years. They topped the Grand Prix Special at the Millers-USET Grand Prix Dressage Championships at Gladstone (New Jersey) in 1989, during their first season at Grand Prix and had to turn down offers for half a million dollars to keep the ride on the horse, finishing as reserve champions behind Robert Dover and Walzertakt.

The freestyle started appearing on schedules in the 1980s to instant acclaim, sending the community cramming to figure out how to ride them, judge them, choreograph them and arrange music for them.

In Other Sports

In 1980, the United States sent a team to attend the World Driving Championships in Windsor (Great Britain) for the first time. Editorial staffer Patricia Chelberg took a leave of absence to serve as a groom for Clay Camp’s four-in-hand at the World Driving Championships, setting the precedent for Associate Editor Molly Sorge to head to the Burghley Horse Trials (England) in 2004 to groom Test Run for Kim Meier. Unfortunately, Camp had to retire on marathon after overturning his vehicle, one obstacle from home, and the best result came from Deirdre Pirie, who still finishing well down the standings. (Team stalwart Jimmy Fairclough was described as “inexperienced” that year.)

Read about all the decades of the Chronicle: the 1930s and 1940s | the 1950s | the 1960s | the 1970s | the 1980s | the 1990s | the 2000s