As a 20-something amateur rider in the 1970s, Sherry Robertson didn’t have much to spend on fancy show hunters, so she spent a lot of her time on the backstretches of racetracks in the northeast searching for her next top mount. In those days, the racetrack was the place to find a prospect, even for top riders like Rodney Jenkins.

As Robertson strolled the aisles of the barns at Dover Downs (Del.) one chilly winter afternoon, she came across a tall, dark and handsome bay Thoroughbred gelding.

Robertson asked the trainer to take him out of his stall so she could have a look. Unable to trot him because he was so excitable, the trainer walked him up and down a few times.

“He said he had a track record at some leaky-roofed track in upstate New York and he was attractive,” Robertson remembered. “But he was wrapped and I asked what was under the bandages and he goes, ‘Well he bowed again.’ I thought, ‘Oh God!’ He said he would be fine and that he’d had him and lost him and claimed him back and that he was a good horse. He was at the end of the road as a race horse and he said if I took him and gave him some time, he would be sound.”

While the 17-hand Corinth was a bit too tall for her, Robertson decided to take him for the $350 the trainer was asking, but not without a caveat—he said she had to take his palomino lead pony as well.

“I said, ‘I don’t really have any use for a palomino lead pony,’ but he said, ‘No, no, you can’t have one without the other,’” she recalled.

Robertson handed the trainer the $50 she had in her pocket and told him she’d be back in the morning with the rest to pick up her new project and his buddy.

A friend at the track encouraged her to bet on his horse for fun that day and Corinth’s trainer had told her of a horse he had running that he thought might win, so she bought a $10 double ticket on both horses.

They both won and her double ticket paid $500, so in the end, Robertson walked out of Dover Downs that day with two free horses and a little spare change.

ADVERTISEMENT

When she came back the next morning, Robertson had a plan. “I thought, ‘I’ll just zip in there, get them to load the bay horse first, then I’ll shut the truck and leave before they can get the other one out,’” she said. “Well, they were quicker and smarter and brought the palomino out first because they knew I didn’t want him!”

For anyone familiar with Robertson, this story isn’t out of the ordinary. Now 64, she’s made many of her own hunters and jumpers throughout the years and has earned tricolors across the country on horses like Corinth in the amateur jumpers, and Lyphard Cay, Pacific Trade, and The Pink Think in the amateur-owner hunter division.

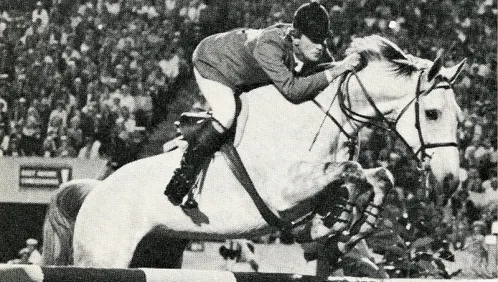

What I assumed would be a quick conversation about a photo of Corinth that I’d come across online turned into a 45-minute conversation, filled with stories of horse trades, rags-to-riches show hunters and the glory days of the Thoroughbred in the show ring.

Robertson trained with the likes of Debbie Stephens, Katie Monahan Prudent and Rodney Jenkins throughout her riding career and she’s a veritable encyclopedia of hunter/jumper knowledge and good horsemanship.

“It always sort of makes me laugh when people say you can’t do the sport if you don’t have millions of dollars because you can,” she said. “You have to be very careful and if you’re not smart about the horses, you have to have somebody who will help you be smart about it, but you can buy horses at the racetrack. We bought a lot of them—Idle Dice came from the racetrack, Number One Spy came from the racetrack. We used to go every couple of weeks because we had people who would keep an eye out for us.”

Robertson relished finding that diamond in the rough at the track and if she took a chance on one that didn’t have a good jump, she could often find it another job or return it in better shape to the track.

“If they didn’t jump well, I would keep them two or three weeks at the farm and turn them loose in the round pen or lunge them, do their teeth and send them back to the track,” she said. “The majority of them were winners the first time they went back because they were fresher and sounder.

“I would fool with them and after a while, take them down to Rodney Jenkins and he would sell them, keep them, whatever,” she continued. “The business has changed a lot because it’s certainly easier to get on a plane and invest seven days going to look at horses that you’re going to be able to drag to the ring, rather than going to the racetrack and picking out horses that you might not even get to jump. We had some people that would let us jump them at the racetrack, but that’s really what changed the Thoroughbred versus the warmblood. It’s a time thing.”

Robertson took that time with Corinth, as she did with each horse that came through her barn, and he flourished into a great jumper and partner.

ADVERTISEMENT

“You couldn’t take two hands and reach around the bows [when he came off the track,]” she said. “Both his front legs were that big. I was just really careful.”

Corinth received a few months off to let his bows settle and started a short-lived career in the hunter ring before transitioning to the jumpers.

“He was a little big for me and a little tough to be a hunter,” she said. “He wasn’t one that came out and loped around with a loop in the reins. That’s when I figured I’d do him in the jumpers. He won pretty much. I don’t remember great successes, we’re talking a long time ago!”

Corinth could be nasty in the stall, but when he went to work, he was all business. Robertson rarely rode him in warm-up classes or lots of lessons, choosing to work on flatwork, use poles and riding through the country, a skill instilled in her by Jenkins.

“I’ve had a bunch of horses that have been not expensive,” she said. “Sometimes you just have to take your time and try to sort it out and it doesn’t happen really fast. I’ve always done my horses at home by myself. I meet my trainer, whoever it is at that point, at the ring or if we were in Florida I might have a jump around before the show, but I’m not somebody who really trains on their horses a lot. My horses rarely jumped in between horse shows. By doing it that way, the ones that weren’t the soundest ones lasted longer. They’re like cars—they only have so many miles, and if you drive fast and drive them hard, how long does your car last? Not real long.”

After about four years, Robertson lent Corinth to a professional rider’s son in New York, who rode him in the equitation finals at the Pennsylvania National and the National Horse Show (N.Y.), before going to live with an adult amateur nearby who rode him in the jumpers and retired him to her farm to live out his days.

Robertson began focusing more on hunters and now lives on a small farm in Edgmont, Pa., with her husband of nearly a year, top jumper owner Harry Gill, whom she first met 44 years ago at a horse show.

A knee injury prevents her from riding seriously these days, but she looks back on her days with Corinth with a smile.

“I was good with the hunters, but I was not a great jumper rider because I never had anybody to teach me to be a great jumper rider—or the right horse. I did [Corinth] and it was fun, but it’s not like I was going to be Katie Monahan by any stretch of the imagination!” she said with a laugh.