Our columnist explains how he goes about the process of picking out the next international show jumping champion.

Selecting a young horse as a prospective international jumper is a topic that I never tire of talking about, learning about or doing.

I think it’s necessary to predicate this column by saying everything I’m going to say doesn’t matter, as there are always exceptions. Additionally, I don’t presume to think that I’m always correct. Picking out young horses is high risk at best, and people don’t hire me to choose their horses because I don’t make mistakes; they choose me to pick out horses hoping I make fewer mistakes than some others. The fear of making mistakes will certainly preclude one from finding a diamond in the rough.

The whole process should be fun. If it’s not fun, one may put undue pressure on a horse trying to force it to be something that it’s not. Never forget horses don’t know how much we paid for them. If we overpay, it’s our fault, not theirs. If they aren’t what we dreamed of, the dream is our fault, not theirs. If we don’t look at each horse through the eyes of maximizing their potential and expecting nothing more, that’s our fault, not theirs.

Buying horses must be looked at as an exciting adventure into unknown depths of despair and unimaginable heights of elation. The pride of developing a young horse to its maximum potential will be far more meaningful to the true horseman than any monetary gains.

Attitude And Appearance

Now down to the nitty-gritty: the details of horse selection. When my wife Beezie and I are looking for young prospects, probably the most important characteristic that we try to measure is aptitude: a horse’s ability to be trained, his ability to learn, his ability to respond to the rider and his temperament while doing so.

Accepting training and learning are two different things. Some horses will acquiesce to training rather quickly but not retain that training, so while being tractable, they have no retention. Horses that aren’t good learners have been my second most disappointing forays into young horse development. The only risk bigger than a non-learning horse is a lame one.

During the trial it’s very important not to overface a horse but to mildly challenge its rideability, scope, carefulness, character and soundness in a limited enough manner that a realistic assessment can be made as to how much improvement the horse makes over the normal two-day trial.

Day 1 consists of 15-20 minutes of flatwork and a moderate amount of jumping. In the flatwork, we will examine soundness through multiple changes of direction and multiple circles in each direction of varying diameters at the walk, trot and canter. If possible, it’s also valuable to ride the horse and see it move on varied surfaces (grass, all weather and a hard surface). While it’s ultimately the veterinarian’s responsibility to determine the soundness of the horse, you can add valuable insight and make his job more complete by being objective about the horse’s soundness through the trial.

Particular attention should be paid to the horse’s movement around the barn when he’s cold and after he’s warmed up. The jumping on the first day consists mostly of a cursory evaluation of his raw jumping ability and the rider developing a relationship with the horse. This should be done over fences that are well within the horse’s ability for the level of training he’s had. I’ve seen far too often uncomfortable riders overfacing themselves and the horse on the first day. Give yourself and the horse a chance. It’s so important to have a constructive first day because it allows you to get a clear view of the horse; it allows you to sleep on it and not filter through a bunch of garbage on the second day. You don’t need to test everything out the first day; you need to get impressions.

ADVERTISEMENT

After you’ve reflected on the impressions of the first day, the horses will show themselves very clearly when you add to the test on the second day. Day 2 consists of flatwork again and more rigorous jumping. It also consists of testing the impressions that you got from the first day. Day 2 is designed to test the questions of the prior day.

When I first meet a horse, I’m very interested in trying to notice as much as I can about his conformation, the shape and consistency of his hooves, the look in his eye and the general appearance. What’s its body type, heavy or light? Does it have spur marks? Are there any blemishes on the legs, or for that matter, anywhere on its body? Before even seeing a horse in action, I like to see him in the barn and attempt to develop a relationship with him. If a horse has severe defects in its conformation or feet, we may consider not even trying the horse, that’s how important I feel conformation is.

This isn’t a column on conformation; there are a multitude of books that describe this subject beautifully.

A few of my preferences are that I like a Thoroughbred type horse with good feet. Pay careful attention to whether the horse wings, paddles or toes in or out. I don’t mind sickle hocks, and I look in particular for horses that are wide in the hips. The length of the back is something that I withhold much judgment on until I’ve seen the horse move and jump. The neck should be light and well shaped. The head, ears and eyes are also very important to me. I’m not big on cute horses; I much prefer a workmanlike attitude and expression. Again, the eyes are very important to me; they should be kind. I’m not big on horses with squinty or small eyes. The ears should move freely, and again, I don’t like overly cute. I would prefer when the ears are set slightly to the side, not too close together. The horse should have a mouth that’s able to readily accept the bit and while not being a dentist, you should look inside the mouth and make sure the bite looks fairly normal.

I’ve talked a lot about the head, but I truly believe the eyes are the window to the soul. When I look at a whole horse I’m very interested in proportions. For me, an ideal jumper prospect is very powerful behind and fairly light in the neck and shoulders. When looking at the overall horse, I think it’s important not to get wrapped up in too many specifics. At the same time one must take another opportunity to identify any real deficits in the horse.

The movement of the horse is very important. The walk should be loose and long. The hind leg should travel well up under the horse’s body, although overstepping with the hind legs is not something that I think should be valued. At the trot, one can start to measure the horse’s balance. It should be free, and soundness is absolutely crucial. At the canter, one can observe much more about the horse’s balance and temperament. Remember when trying very green horses that lead changes are not crucial, but defects in movement or temperament that could cause difficulties in training lead changes should be noted.

The Jump: Don’t Touch It

After making an assessment of the horse’s general appearance and movement, we go on to jumping. I like to make the jumping tests fairly easy for the horse’s level of training. I want to see the horse’s best, not its worse. I’m not interested in testing the horse; I’m very interested in giving the horse the opportunity to show its best.

Analyzing the jumping itself is shockingly simple. Germany’s Hartwig Steenken had a great string of horses in the late ’70s, and when asked how he picked them, he simply answered, “They should go from one side of the obstacle to the other without touching.”

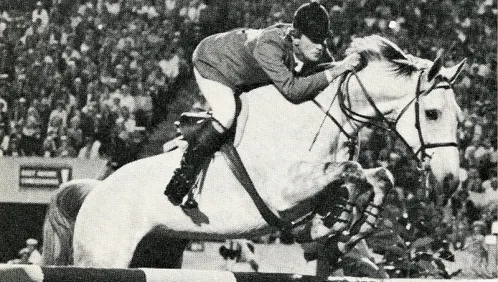

John and Beezie Madden selected Authentic as a young prospect, and he went on to win two Olympic team gold medals and team and individual silver medals from the 2006 World Equestrian Games. Photo by Molly Sorge

It’s good if they jump high; it’s bad if they jump low. It’s good if they don’t touch; it’s bad if they do. It’s good if they’re brave to the fence; it’s bad if they stick off the ground.

I’m particularly interested in how a horse leaves the ground. The horse should make a strong statement as he leaves the ground, like an explosion. Where the legs go after that is not of particular concern to me. Horses learn to put their legs in the right places; the key is that they launch like a rocket off the pad with the withers coming up and back toward the rider like a battering ram. The trajectory of the jump is very important to me. If the horse leaves the ground well and jumps up with its withers, its center of gravity will go up, and it will have a good trajectory over the jump. At the middle of the jump, I’m interested in seeing that the horse is round, that he looks athletic and that his body doesn’t freeze up, getting stiff in the air.

The landing should be forward and light. I don’t like when horses land “dead” or in a heap. Doing so makes it difficult for rideability on technical courses. On landing, I also like to be attentive to grunting or noises. If the horse sounds heavy, it probably is, and this is crucial to long-term soundness. It’s important to observe the horse’s balance on the stride after landing. It should quickly reestablish its balance and should not have jumped so exuberantly that it lands on its nose. Notice also how quickly the horse reestablishes a rhythmic gallop.

ADVERTISEMENT

Remember, a consistent rhythmic gallop is crucial when looking for horses that are easy to ride.

I like blood horses, horses that have a lot of energy and are light on their feet. It doesn’t bother me if a young horse is fresh; it does if they’re dull. In the process of selecting horses, it is very important to try to stay objective. We all do this because we love horses, and it’s very easy to fall in love.

The Business End

One needs to remain focused and to follow all of the requisite procedures. Before even trying a horse, understand the process of trying, vetting, bill of sale and payment.

The process for me is first scouting the horse: identifying a prospect through other professionals, seeing it in the ring or watching videos. Once you’ve identified a horse you’re interested in, the price should be determined, and you should try the horse based on the asking price of the horse. Commissions, price, etc., should all be clear.

I know and am confident in the process we use. That is, taking care of the business end of things first. As a buyer, I demand this process be followed professionally and that I be given the time to follow this process. I will not be rushed. Threats of other buyers, etc., go nowhere with me. I demand that once we begin a deal, we’re allowed to follow this procedure to the letter in a timely fashion. Remember, it’s very easy to buy a horse, not so easy to sell.

If, after trying the horse, one chooses to proceed, the pre-purchase exam becomes crucial. I don’t know any perfect horses, and there will be findings on nearly every horse. For me, the key is to know what you can handle and what you and your veterinarian are nervous about handling. It’s also key to keep in mind what the horse’s eventual job is and to assess that against potential veterinary issues. If I’m buying a horse for resale, the pre-purchase becomes even more important because you know the horse will face the same scrutiny when you try to sell it.

The whole process is really a lot of fun. None of the things I’m saying are hard, fast rules, and really to be successful you need to put all of the thoughts and ideas and observations together and come up with an overall picture. You’ve got to love the overall picture. You have to look at the details carefully and then forget the details and focus on your overall view.

The best advice I can give is never forget that you really need to love the horse. There will be good days, and there will be bad days, and my final decision making questions are quite simple: “Do I have to have him? Do I really love him?” If so, good luck with your new horse.

John Madden, Cazenovia, N.Y., is married to international grand prix rider Beezie Madden. Together, they operate John Madden Sales Inc., where they train horses and riders. The horse business has encompassed John’s entire life, and in addition to his business he was the Organizing Committee Chairman for the Syracuse Sporthorse Tournament (N.Y.) and is on the U.S. Equestrian Federation High Performance Show Jumping Computer List Task Force. He began contributing to Between Rounds in 2008.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to read more like it, consider subscribing. “Shopping For The International Jumper Prospect” ran in the June 13, 2011, issue. Check out the table of contents to see what great stories are in the magazine this week.