|

A lifetime in the horse industry has taught this well-known hunter breeding handler much more than how to stand a horse up on the line. Dowell “Junior” Johnson never doubted horses would be his livelihood. From age 5 he was obsessed, fitting school in around weekends, weeknights and summers spent at the barn. |

Now one of the best-known handlers on the hunter breeding circuit, he’s made good on that childhood passion. With three Leading Handler Awards from the Devon Horse Show (Pa.), in 2009, 2011 and 2012, he’s achieved some of the biggest accolades in the business.

Last year he held the line on Westfield, the 3-year-old Thoroughbred gelding who earned the overall reserve championship in the Sallie B. Wheeler/U.S. National Hunter Breeding Championship. Bred and owned by Meg Valnoski, Westfield has been in Johnson’s program from the beginning.

But Johnson won’t spend any time bragging about his achievements. Soft-spoken and self-effacing, he’s more likely to tell you that he’s still working on claiming the coveted Best Young Horse title at Devon. Then he’ll move the focus away from himself and introduce you to the newest four-legged resident in his barn, a simple but ample facility in Moseley, Va., that he rents with his business partner, Laurie Pitts. Together, they run Junior Johnson Training and Sales, bringing up horses for the hunter breeding classes as well as training and developing performance horses.

Walk with Johnson as he leads a young horse out to a paddock behind the barn. When the energetic baby starts to object, Johnson waits patiently for the youngster to follow him again. He has no tolerance for drama, just a pause before moving forward.

That small action, that small pause in motion before the young horse is safely delivered to the pasture, shows Johnson’s attitude toward just about everything: When faced with adversity, pause, breathe and move forward.

An Early Education

Whether it was learning to ride with Frances Rowe, working with Kenny Wheeler, warming up horses for Rodney Jenkins or taking clinics from industry legends, Johnson received an exceptional education as a young horseman.

|

|

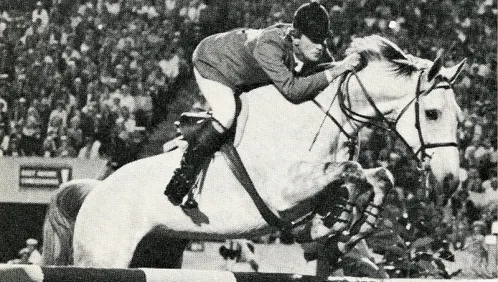

In 2012, Junior Johnson earned his |

“I couldn’t wait to get home from school so I could go to the barn,” said Johnson. His father, the late Dowell Johnson Sr., worked for Rowe at Foxwood Farm in Crozier, Va. She took Junior under her wing and taught him how to ride when he was 5.

The oldest of nine children, Junior was one of three who embraced the equine culture. In addition to riding show horses, Junior also worked race horses in his youth.

“Frances wanted me to get my trainer’s license and go to the track, but I didn’t ever want to do it,” said Junior. “I couldn’t afford lessons growing up, but she gave me lessons. She gave me opportunities to ride with Gordon Wright and Bert de Némethy, people like that. They would have clinics, and I would ride in the clinics.”

Not only did Junior learn how to ride with the best, he learned the ins and outs of stable management, training and grooming. While working for Rowe, Junior traveled to shows with famous jumpers like Old English and Balbuco.

What Could Have Been

If Junior’s skin had been another color, he might have been the one in the show ring aboard some of those historic horses.

Although he’s too diplomatic to give many details, Junior concedes that racism has always been part of his life in his chosen career. It was more overt in his youth, when he was riding and grooming for Rowe. Junior stayed out of the spotlight at horse shows.

One year Rowe’s top rider broke her collarbone at the Keswick Horse Show (Va.). Rowe asked Rodney Jenkins to ride the horses.

“But Rodney had so many horses back in the day,” said Junior. “I schooled them and got them ready, and he’d take them in the ring, but I would not show. I told [Rowe] I would not show.”

At some shows, Junior and other black grooms were told they couldn’t warm up horses on the show grounds. “Fine if you do it at home, but you cannot school a horse at a horse show. It was bad; it was really bad,” said Junior.

Those experiences as a young man were very much in Junior’s thoughts as he pondered his future in the equestrian industry.

“That backed me off a lot because I didn’t want to deal with that, the pressure of it. I guess it made me good at what I’m doing now because I didn’t give up. I kept going with it,” he said.

In the late 1960s, Junior was invited to train at the U.S. Equestrian Team headquarters in Gladstone, N.J., and Rowe even offered him horses to ride, but he decided to stay in Virginia.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I could have gone to Gladstone, could have rode there, but I didn’t choose to do it because of my color. Back then it was tough, really tough,” he said. “If I had kept doing it when I was young, I could have been good at it. But if you stop when you’re young and say you’re coming back to it, it’s not there. You’ve got to do it all the time, every day.”

Even now, Junior makes an effort to steer clear of judges he feels unfairly penalize his horses.

“I’m not saying all of them, but a handful of them are a pain in the ass,” he admitted.

Pitts concurred, adding that she’s noticed patterns over the past few years.

“There are some judges, several of them watched Junior grow up as a black groom in the South, and he can’t win under them no matter what he brings,” she said. “And we don’t take bums to the horse show. We only take ones we think we can win with. There are certain people we just cannot win under.”

Despite any misgivings, Junior keeps his eyes forward and puts one foot in front of the other.

“I try to do the best I can under that judge,” he said.

However, he never felt prejudice at home. “I grew up around wonderful horses and wonderful people,” said Junior, adding that his son, hunter/jumper trainer D.J. Johnson, had a different experience showing as a young man.

“He don’t pay any attention to it, and that’s the good part. He keeps going forward, and that’s what you got to do,” Junior said. “But it’s still there. As successful as I’ve been, I can tell.”

Bringing Up The Babies

Junior turns 62 on April 6, and he hasn’t been in the saddle much over the past decade.

But he still loves the training process from start to finish.

After leaving Foxwood in the late 1970s, Junior went to work for Kenny and Sallie Wheeler at Cismont Manor Farm in Keswick, Va., and stayed there for 10 years.

It was at Cismont that Junior got his introduction to the hunter breeding classes.

“I broke all the horses at Cismont,” Junior explained. “Everything was babies when we bought it. I like to look at them, and I like to see them grow up, see them be better horses as they get older and older.”

He never had formal training in showing on the line. Instead, he learned by watching Kenny, one of the most successful handlers in hunter breeding history.

“Cismont really got me into the babies, and then Karen Reed gave me the opportunity,” said Junior.

Reed owned Amber Lake Farm (Va.), where Junior worked after a short year at the Jacobs family’s Deeridge Farm in New York.

At Amber Lake, Junior dove head first into preparing young horses for the breeding classes. One of his most cherished keepsakes is the ribbon he collected in his first Devon win. He keeps it neatly framed with a photo of himself and Secret Blade, who won the non-Thoroughbred 3-year-old class in 1994.

“That was a favorite. It was something that I had wanted to do,” he said. “It started building and going forward from then.”

Over the years, Junior’s noticed the shift in breeding classes from Thoroughbreds to warmbloods, and he laments the lack of entries in the Thoroughbred classes. Yet, he doesn’t prefer one more than the other.

“I like both; I’ve been successful with both,” he said.

He thinks the shift stems more from laziness than actual quality. “A lot of people just have one breed, and that’s the warmblood. But a Thoroughbred horse is just as good,” he said. “People don’t give them a chance anymore. They don’t want to work at it. They would rather go to Europe and get those horses already going.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Junior worked for Reed until he and Pitts started their own business in 2006. They became friends in the 1970s when Junior was still working for Rowe, and Pitts groomed for Joan Boyce. She went on to groom for Conrad Homfeld for several years before leaving the equine industry.

In 2004, Pitts started helping Junior at horse shows as a way to get back into the hands-on care.

“My passion has always been taking care of horses,” Pitts said.

The Perfect Business Arc

Unlike trainers who see the in-hand classes as the end game, Junior looks at them as the starting line for young horses.

“A lot of them, once they finish their 3-year-old year, you never see them again. A lot of [people] don’t realize [they] go do different things,” Junior said. “They might go do dressage; they might be jumpers that we don’t hear about. [Some] get hurt, and you don’t hear nothing about it. A lot them show at the little one-day shows and stuff like that.”

After the horses graduate from hunter breeding, Clem Clements breaks them, and Meg Graham shows them under saddle.

The spacious barn aisles at Junior Johnson Training and Sales are quiet. Junior and Pitts don’t take boarders. Walk in and the only sound you’re likely to hear is the soft munching of hay and the occasional snort or sigh of a contented young horse.

“I do all the grooming, all the mane pulling, braiding, trimming. Junior, he trains them,” said Pitts. “Junior’s not a kissy-face, lovey type of guy. He loves the horses and respects them. I’m the one who makes them into nice pets.

“We have a dust up every now and then, usually because either he’s telling me how to do my job, or I’m telling him how to do his job,” Pitts joked. “Once they’re trained, once they learn what he tells them—that they need to stand still and they need to stop a certain way—we don’t drill them. Their practice is in the show ring.”

While Junior is best known for his accomplishments on the line, he and Pitts are trying to grow the performance side of their business.

“Our greatest joy is taking them from showing in-hand, then breaking them, starting them over fences, and then taking them to their first horse show,” said Pitts. “To us, that’s the perfect arc for our business. Having said that, we unfortunately don’t get a lot of that.”

Instead, babies often go home with their owners during the off-season, leaving the barn light on clients. “People don’t know that I do train horses,” Junior said.

A Family Tradition

Horse fever seems to run in the Johnson blood, and every summer a member of the newest generation of Johnson horsemen joins the team.

“My grandson, Deshawn, he’s the next generation after D.J.,” Junior proclaimed. Tonya, Junior’s older child with his wife, Jackie, dabbled with the horses when she was younger, but she doesn’t ride now. However, her son Deshawn frequents the barn whenever school doesn’t keep him away.

But instead of showing horses either in-hand like Junior or under saddle like D.J., Junior guesses the 14-year-old might go down a different path.

“I think he’s going to be a course designer. He’ll sit here, and he’ll make a course out,” he said.

Junior shakes his head in amazement as he looks out the window to the large outdoor arena across the driveway. When he describes the way Deshawn sees the lines, distances and intricacies of a course, it’s clear that no matter what Deshawn does, his grandfather will be proud of him.

“I tried to give him lessons when he was 7 or 8. He’d never want to ride. He’d ride, but he’d rather go tack a horse up and go out walking cross country,” said Junior. “I didn’t force him. I said, ‘If you don’t want to ride, you don’t have to ride.’ If you force them, you just back them up.”

And just like Junior approaches a young horse, he doesn’t push, just pauses and moves forward.